Their extreme conservatism may have helped captives escape the recession relatively unscathed, but is it time to take the bull by the horns and make their investments work harder? As Helen Yates is told, fortune still favours the brave

Captives emerged from the economic crisis in better shape than many other financial institutions, due in large part to the bearish approach of their investors. The few that had a higher proportion of their investment portfolio in equities – generally those captives writing longer-tail lines of business – were slightly bruised, but out of the 200 captives rated by AM Best, only one was downgraded. This was a large energy group captive, which made the mistake of offloading its investments at the bottom of the market. Even then, it was only downgraded one notch.

“We had companies that were down 10% or 15% – one was down 18% – but they didn’t sell their equities and these then recovered substantially by the end of the year,” AM Best vice-president Steven Chirico says. “If you look at the actual low percentage for the year, yes there were some sweaty brows in boardrooms, but their statement for the year wasn’t so bad.

Captives tend to be very conservative and the 10%-20% that do take risky investments are playing with extra money. Some captives were able to lose 15% of their investment portfolio and still not be in trouble with us from a BCAR [Best’s capital adequacy ratio for insurers] perspective or a rating perspective.”

There is a fundamental difference between captive insurers and commercial insurers in how they approach the investment side of their balance sheet. For commercial entities, the investment return is an essential part of the overall profit and often, although this is not always advisable practice, a supplement to underwriting premiums during a soft market.

For captives, there can be no cashflow underwriting. “It’s about maximising the extra money off the portfolio, but that’s nowhere near as important as the underwriting piece,” Chirico says. “And that’s true even for the ones that have more aggressive portfolios. It’s the cream on the top of the sundae – it’s not the sundae.”

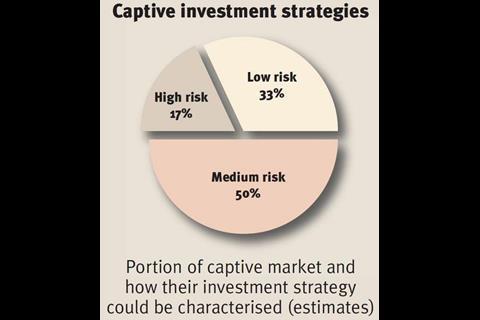

Within the captive family, there are a range of approaches to investing, some riskier than others, but all falling within a more conservative band compared to commercial insurers.

Around a third of captives are the picture of conservatism, with the bulk of their portfolios invested in cash and secure, highly rated fixed income securities. “They tend to be more the group captives – particularly the smaller ones that seem to get very clear board direction that they don’t want them playing with their money, they just want to invest it safely,” Chirico says.

The second group, representing around 50% of captives, are one step closer to a higher return; their bond investments may be slightly more risky, including, say, corporate bonds with BBB or A- ratings. They may also invest in stocks, such as mutual funds or exchange-traded funds, which reflect a diverse mix of blue-chip non-correlated equity holdings. Only a small number of captives actively seek to maximise their investment return and have a portfolio akin to a commercial insurance company. While a high proportion of their investments remain in fixed income, around 30% is invested in equities and there may be some use of derivatives, although these are mainly used as a hedging tool.

“These tend to be single-parent captives and larger group captives,” Chirico says. “They tend to use their extra money by taking 5% to 10% of their portfolio and dumping it in a fairly risky investment. But these captives are in the minority and tend to be fairly well funded.”

MIX AND MATCH

As captives mature, they should look to build a more balanced portfolio, where they more accurately match their assets and liabilities.

The idea is that those underwriting short-tail lines of business, such as property, should take a shorter-term investment horizon on their investments, while those writing long-tail lines should take a longer-term view.

“A captive that writes just property is going to know its claims early and settle its claims early, so it needs to have a portfolio that is a lot more liquid than one that writes workers’ comp or medical malpractice or one of the really long-tail lines,” Marsh IAS chairman and managing director David Ezekiel says.

The captives with long-tail liabilities were most affected by the downturn because their investment portfolios contain higher equity weightings. Despite recent performances, Ezekiel thinks a long-term view is the right way to achieve a balanced investment portfolio.

“There’s always this trade-off between what one knows one should do – invest for the long term – and what one is often forced into, which is short-term considerations in order to protect surplus and make sure one meets the regulatory requirements on a continuing basis,” he says.

“The more successful investment strategies are those that come from the more mature captives, which have built up surplus and can withstand the volatility that comes with long-term investing. Typically, in the early years, while a captive is building up its surplus, it is extremely risk averse and focuses largely on fixed income – although we’ve now learnt even that can bring its own dangers. But as it builds up free surplus, it then has the ability to move to a balanced portfolio, which will contain an allocation to equities and perhaps a smaller allocation to the alternative market.”

REFOCUSING

Ezekiel is concerned that captive managers could become too conservative in investment as a knee-jerk reaction to the financial crisis. A number of entities that cut their losses during the height of the crisis have yet to pick up where they left off. “You’ve got a lot of people now that were frozen in the headlights after the downturn,” he explains. “They suffered badly and they got out and went into either very short-term fixed income or cash, which is earning them nothing right now. They’ve seen a market that has charged up and now think it’s overbought, so they are still finding it difficult to make the decision to get back in.”

Ezekiel predicts captive owners and managers will refocus on their core business – underwriting insurance risks – with investments seen more as a by-product. “There has been a mindset change and people will, for a short period if history is any guide, concentrate on the underwriting and reserving side,” he says. “They will continue to have a sensible investment allocation but will move away from trying to make the investment side some sort of profit centre and put it back to what it should be: as part of the overall operation of the company.”

He also argues that captives spend too much time on manager selection and not enough time on asset allocation. “The allocation decision ends up contributing about 85% of your return and the manager selection decision only about 15% of your return. So we try to get our clients to focus much more on the allocation decision.”

Post crisis, some captives are questioning whether they are getting value from their investment manager. Yet these investment managers are not necessarily focused on maximising return, as they tend to be given fairly conservative guidelines by their clients and have a tendency to work to benchmarks.

TIME TO DEFROST

Kane consultant Clive James says: “I think you can do a lot of this work internally within your organisation, looking to see how the corporation runs its own areas in terms of matching its assets and liabilities and applying some of that to the captive.” He takes a different stance on captive investments, arguing that captives should be more aggressive. “A lot of captives have historically been too conservative.

They need to be more proactive in terms of matching the assets and liabilities, because a lot of the assets are short term and a lot of the liabilities are long term, and the two aren’t matching up as they should be,” he says.

“I don’t think we can ever get away from the idea that the investment portfolio will be conservative, but there’s a lot of opportunity to move it away from the standard practice that happens at the moment. People do need to be a little bit more aggressive, because the chief financial officer of the parent company will look at the captive and say: ‘well, what’s the point in doing this if we’re not maximising our return?’”

With the tumultuous days of the financial meltdown still fresh in the minds of the boards of the parent companies, captive investment strategies are likely to attract closer scrutiny going forward. Whereas in the past this responsibility might have been handed to an investment manager and left on autopilot, there is now a desire to have a closer involvement.

Some see this as an opportunity for the captive managers. Helping clients better understand how to monitor and extract value from their investments could be another string to their expanding bows.

Postscript

Helen Yates is a freelance writer