Captive insurers are increasingly underwriting more esoteric risks not adequately catered for by the commercial insurance market

From contingent business interruption, cyber liability and reputational risk to product recall, intellectual property (IP) and environmental liability, many of today’s emerging risks are hard to indemnify. The commercial insurance market responds with varying degrees of innovation, but some captive owners are opting to self-insure.

The difficulty is in structuring products for intangible assets such as reputation and IP. The solution, as is often the case in insurance, is adapting existing covers and combining that with a strong approach to risk management and business continuity. But even where products can be successfully structured, a lack of claims history and underwriting data can restrict breadth of cover and increase the pricing.

Here’s where the captive comes in. “There’s always cover at the top end of the market, the issue is at the lower end,” says Clive James, group chief operating officer at Kane Group. “With product recall, for instance, the reinsurance market will look at past experience and risk management and so the captive may have to pick up a higher layer additionally before it can access the reinsurance market.”

Kane has worked with clients to insure product recall, supply chain, export liability, political risk as well as some forms of fraud insurance. James has seen increased interest in IP. Exposure to IP infringement has increased in recent years owing to patent trolls. “There’s certainly an interest on the IP side moving forward without question, especially for high-tech companies,” he says.

On the risk radar

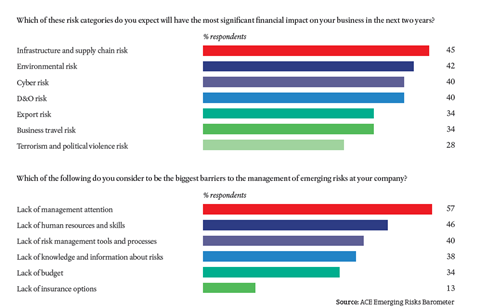

The results of surveys are a good indicator of which emerging risks are high on risk managers’ radar. Supply chain and infrastructure, environmental, cyber and D&O were among the emerging risks expected to have the biggest financial impact on businesses in the next two years, according to a ACE survey.

One reason for risk professionals’ concern are the plethora of cautionary tales in the headlines. Costly cyber attacks and data breaches have affected multinationals such as Sony and Google recently, while global supply chains feel the ripple effect from natural catastrophes such as the Tohoku earthquake and Thai floods. Deepwater Horizon cost BP more than $40bn (€29bn) and the reputational fallout from the Gulf of Mexico oil disaster continues (in excess of the $700m limit of BP’s captive Jupiter).

Compounding exposure to these risks is increasingly stringent regulation. In Europe and the UK, rules surrounding privacy and data protection are coming into line with those in the US, including mandatory notification when protected information is compromised and heavier fines for failing to protect data.

The costs of returning the environment to its original state after damage or pollution are ten to 40 times higher under the EU Environmental Liability Directive (2004/35/EC) than in the past, according to a French regulator’s estimate. As a result, environmental insurance is increasingly viewed as low likelihood, high significance cover. “Some risks, such as cyber risk, are relatively new,” says ACE European Group president Andrew Kendrick, in his foreword to the Emerging Risks Barometer 2013. “Others, like environmental and D&O risks, have been around for a long time, but have taken on a new dimension owing to social, economic and regulatory change.”

Brand and reputation

In a more global interconnected world where information is shared in real time, the reputational fallout from an event, be it a cyber attack, industrial accident or PR blunder can be catastrophic. Brands built up over decades can be undermined in just hours when negative press is shared with an increasingly informed and activist consumer base.

Organisations able to respond rapidly and appropriately to adverse circumstances are most likely to come out the other end with their reputation intact, argues Airmic’s Roads to Resilience report. “If you get it right you don’t just minimise the damage and the negative impact, you actually gain profile for your brand and you enhance your reputation because you have behaved appropriately when something dreadful has gone wrong,” says report author and Airmic technical director Paul Hopkin.

But brand and reputation are inherently difficult to indemnify. “There are two problems with reputational risk,” says Dominic Wheatley, managing director of Willis Management (Guernsey) Ltd. “It is intangible and therefore determining what a loss looks like and how you quantify it within the parameters of indemnification is quite difficult. Because of that there’s very limited data to work on so actually pricing the risk properly is quite difficult to do.”

To date, many reputational products have focused on crisis management, an after-the-event indemnification, which covers the cost of a public relations campaign intended to minimise the fallout of an unfortunate incident.

“That’s very typical of the insurance market to identify a quantifiable element that’s related and to say we’ve got reputational risk cover,” says Wheatley. “When actually it’s not reputational risk cover, it’s just continuing cover for additional costs involved in managing an event.”

“It’s a little bit like cyber risk where they don’t want to deal with the consequences of a major cyber event but they’re happy to pay for the costs of recreating data,” he continues. “What the market tends to do in my experience in these difficult to quantify and define risks is to find an area that fits their business model and design cover around that, and that doesn’t necessarily meet the demand that clients have.”

Some insurers have made significant strides in seeking to measure and indemnify loss of reputation by linking a negative event to loss of customers or falling share price. In this sense, explains Dan Trueman, head of cyber insurance at Novae, it is structured in a similar way to conventional business interruption insurance and triggered by a list of agreed perils.

“We see reputational risk and adverse reputational factors as a form of non-damage business interruption,” he says. “Business interruption following a physical damage issue has been around for a long time and so when we talk to risk managers and explain the concept in that way, it’s quite often easier for them to get their hands on it and to talk to the C-suite in a way that it makes sense for them too.”

Captive incubation

For emerging risk insurance products still in their infancy, one option could be to use a captive insurer as an incubator to build up a claims history and risk profile. “It’s highly unlikely this will be the sole business line going through the particular captive, so we would tend to see these incubators as building up funds for the companies that have a captive in operation and want to see how the captive can participate,” explains Kane’s James. “A high level of risk management thought goes into that. So they would actually then combine it into other areas so it’s a spread of the risk into other areas,” he continues. “Certainly with some of these newer products half the reason why there’s an issue is the potential exposure can be substantial so they’re diversifying with their other insurances.”

Captive incubation has had some success with cyber liability. A captive owner may choose to begin with one or two covers, such as third-party liability and first-party losses, building it up to include areas such as business interruption and reputational damage.

“Cyber risk is being written into captives in a more expanded way than is necessarily available in the commercial market,” adds Wheatley. “There is a period with any new risk where there isn’t good data to make sure the pricing of the risk is correct and the commercial market will always do two things: constrain the coverage to something they find acceptable as an absolute risk and the second is to set the price quite high, and unfortunately that often ends up as a fairly unattractive product.”

“The captive can be slightly less constrained, albeit the claims incurred will be borne by the policyholder, but it has that advantage that it allows some claims history to be built up,” he continues. “One of the difficulties with that can be that the claims history builds up in the captives and therefore doesn’t help the wider insurance community to gain a better understanding of the risk over time.”

But using captives to insure emerging risks doesn’t work for everybody. For many, the answer is to indemnify in the commercial market and manage and mitigate the risk internally. Interestingly, when asked which they considered to be the biggest barriers to the management of emerging risks at their company, only 13% of respondents to the ACE emerging risks barometer voted for a “lack of insurance options” while more than half complained of a “lack of management attention”.

“Emerging risk products develop slowly and the take-up rate is low,” explains Heineken’s global insurance manager Eric Bloem. “This is not

particularly strange as often pricing and capacity are less than appealing. Consequently the products do not develop fast. As capacity is insufficient to address a real issue the risk typically remains on our balance sheet. Moving it to the captive does not add value in our structure and for me, our energy is better spent on managing the risk rather than wrapping it into a captive structure.

No comments yet