As a company, Carillion did practically everything wrong, yet its sudden demise has sent shockwaves through the business community. As regulators trawls through thousands of documents with a view to taking disciplinary action, the inevitable result is an intense scrutiny of directors and officers liability and transparency

As successive inquiries uncover evidence of, in the words of the damning parliamentary inquiry into its collapse, the “recklessness, hubris and greed” that led to the fall of Carillion, the post-mortems are turning into a case study on how not to run a company.

And the investigations are widening all the time, bringing in every entity involved – auditors, executives, directors, consultants and even government bodies accused of failing to act soon enough.

The mis-management cited by the parliamentary inquiry was of such a scale that it may yet lead to further action

against executives and directors. The inquiry recommended that the Insolvency Service investigation into the conduct of former directors “includes careful consideration of potential breaches of duties under the Companies Act, as part of their assessment of whether to take action for those breaches or to recommend to the Secretary of State action for disqualification as a director”.

- Latest trends and developments in the construction industry and how this is changing the global risk landscape

- The fall out and insurance considerations following the demise of Carillion and the Grenfell Tower fire

- Implications for directors’ and officers’

- The value of professional indemnity for complex construction risks

As revelations continue to emerge, they make an inarguable case for directors and officers and other forms of boardroom insurance, even for exemplary directors, as shareholders become more distrustful and more aggressive.

The Association of British Insurers said in a statement: “These types of products, such as professional liability, have always been important for anyone in a senior position in a business.”

Regulators are on the case Evidence of the failures within Carillion is being told in millions of words. A team at the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) is still sifting through tens of thousands of documents – audit files, KPMG’s and Carillion’s emails and company papers – as well as interviewing KPMG and Carillion employees, as it trawls through the final four years of the company’s accelerating decline.

If the FRC’s executive council determines it has enough evidence to clear the legal threshold and bring disciplinary actions, it will do so. The FRC’s main focus is on two former finance directors.

The Insolvency Service, Financial Conduct Authority and Pensions Regulator (TPR) are also on the case. For instance, the Competition and Markets Authority is looking at the audit market to see whether new regulations would reduce the long-standing monopoly of the Big Four.

Stung by criticism levelled in the parliamentary report, the FRC also wants to have its say over audits. The body has expressed a wish to be enabled to issue its own assessments in future on the audits of those companies that are deemed to be on the brink. “We now intend to enhance our focus on the audits of companies that appear to be in danger, and should like this to be combined with an ability to call out what we find,” the FRC has said.

Demanding better stewardship

Taken as a whole, the Carillion collapse has unleashed a fury of forensic analysis that will inevitably lead to a much brighter spotlight being shone on the boardrooms of major companies and will put directors under considerably more pressure.

A probably inevitable consequence of all this activity will be reform of the Stewardship Code. As soon as the FRC has finished a review of the Corporate Governance Code, it will start on the issue of better stewardship. The main purpose is to look at whether the code is sufficiently effective, but also whether companies and investors can engage more constructively with each other. One possible outcome is the obligatory appointment of a class of go-betweens – intermediaries who act as proxy agents between board and investors’ representatives.

“We now intend to enhance our focus on the audits of companies, which appear to be in danger, and should like this to be combined with an ability to call out what we find.” Financial Reporting Council

Carillion’s shareholders say they had little idea what was really going on – and the FRC wants this to change. “Statements by companies in the annual report about their governance can fail to provide real insight, and investors can find them hard to challenge,” the organisation pointed out in July in an update of its progress on the Carillion investigation. As a result, the FRC wants more powers, including the right to undertake a report into the quality of governance in systemically important companies.

Another influential organisation to strike a blow for better corporate governance is the Chartered Institute of Internal Auditors (CIAA), which in September urged the FRC to toughen its proposed principles for large private companies “by more closely mirroring measures contained within the UK Corporate Governance Code for publicly listed firms”. It also wants the regulator to “take charge of monitoring the application of the principles”.

The CIIA was referring specifically to the collapse of BHS, but the failure of Carillion only serves to strengthen its case. “The collapse of both BHS and Carillion highlighted a number of corporate governance shortfalls,” Gavin Hayes, the institute’s head of policy and external affairs, told StrategicRISK, pointing out how that the failure of both companies had a catastrophic impact on their workforce, customers, suppliers and the wider economy. “That’s why, going forward, it’s fundamental that we ensure we have a strong corporate governance framework in place that promotes greater transparency and accountability.”

Hurtling to failure

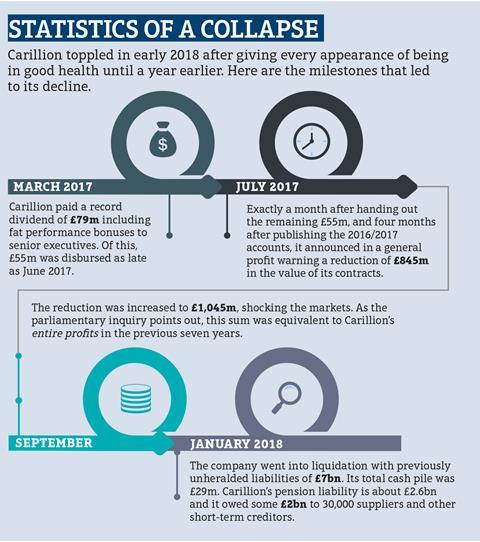

Meantime the parliamentary report should be compulsory reading for risk managers and anybody who holds a position of responsibility in a big company. As the report tells it, Carillion did practically everything wrong over a period of years as it hurtled towards an inevitable failure.

“Its business model was a relentless dash for cash, driven by acquisitions, rising debt, expansion into new markets and exploitation of suppliers,” the report summarises. “It presented accounts that misrepresented the reality of the business, and increased its dividend every year, come what may.”

If that wasn’t bad enough, the report accuses the board of increasing and protecting “generous executive bonuses” while Carillion was beginning to unravel. Conclusion: “Carillion was unsustainable.”

Yet Carillion was a company that prided itself on corporate governance and saw no need for mandatory external reviews. In 2010, on the occasion of a general review of the UK code, the board wrote to the corporate governance unit of the FRC to point out that it was “among the first [publicly listed companies] to adopt a policy of detailed and rigorous board evaluation in 2002, and has used the process to adapt board process, procedure and governance” ever since. The company did not consider mandatory external reviews to be “necessary or appropriate”.

The Carillion board also opposed annual re-election of directors because “it could place in jeopardy the level of continuity essential to the management of a complex business” as well as “threaten the independence of thinking necessary to achieve effective collective responsibility”. At that time, Carillion may already have been running into trouble – it had tripled in size between 2002 and 2010.

A litany of errors

Few are coming out well from the post-mortems in what is turning into a general indictment of big business, causing long-lasting reputational damage by default. The entire system of checks and balances in the economic system has been brought into question by the parliamentary inquiry because they manifestly failed to work in the interests of investors. It’s clear that UK’s biggest resources company, responsible for building everything from roads and hospitals to providing school meals and defence accommodation, had been spiralling out of control for a long time.

Among other deficiencies, the inquiry cites:

- Failures by non-executive directors to challenge or scrutinise reckless executives.

- Systematic manipulation of the accounts “in defiance of internal controls”.

- KPMG’s “complacent signing off” of the accounts over a period of 19 years as auditor; Deloitte’s failures in its role of risk management and financial control as internal auditor; and EY’s “six months of failed turnaround advice.”

- The key regulators – the FRC and TPR – also come in for a hammering for their “feebleness and timidity” in failing to follow up and use their powers after concerns were raised. Both organisations were described as “chronically passive” and requiring “cultural change”. (In its defence, the FRC reminded the inquiry that following the July profits warning it was already investigating Carillion with a view to taking enforcement action when it collapsed.)

The Carillion post-mortems are still under way, but they’re all pointing in the same direction. And that is much tougher oversight of the boardroom.

No comments yet