Supply chain management has advanced in recent years to copy with the complex risk landscape, but there are still lessons to be learned

Supply chains have evolved in an incredible way in the past few years. Twenty years ago, the concept of a supply chain comprised only the logistics involved in delivering a product from supplier to market on behalf of the parent company. In short, goods had to be delivered from A to B and it was not assumed that a supply chain could be exploited to improve margins, revenue and profit in highly creative ways. It took an American professor to see the possibilities.

In 1997, Marshall L Fisher, then professor of operations and information management at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, asked a simple question in an article in the Harvard Business Review entitled ‘What is the right supply chain for your product?’. He held out a tantalisingly attractive prospect: “A simple framework can help you work out the answer.”

Although Fisher did not invent the concept of supply chain, which is as old as transport itself, in the article, he expressed opinions so radical that they brought it closer to today’s views.

Fisher’s essential argument was that supply chains were extremely deficient, despite the new technology available at the time, such as point-of-sale scanners, flexible manufacturing, automated warehousing and unprecedentedly rapid logistics.

“Nonetheless, the performances of some supply chains have never been worse,” he chided.

Dysfunctional

As evidence, Fisher cited a range of disruptive influences that had led to hostile and damaging relationships between the various links along the chain. For example, the US food industry was wasting $30bn (€24bn) per year because supply chain partners were not working together.

Department stores were forced to sell unwanted merchandise at hefty discounts because demand had been so badly miscalculated that the pipelines in the supply chain were full of unsalable products. Worse, their customers were often disappointed because the specific items they had come in to buy were out of stock.

In short, supply chains were largely dysfunctional. According to Fisher (who had already spent 10 years researching and consulting on the fledgling concept of supply chains in various industries, from food and fashion to automobiles), the answer came back to the simple framework, and it is still valid today.

Functional or not

The construction of such a framework started with a bottom-up analysis of the nature of the demand for the company’s products. Without going into unnecessary detail, Fisher found that demand essentially fell into one of two categories. One category was for primarily functional products, while the other was for primarily innovative ones. Both categories required their own “distinctly different kind of supply chain”.

Thus, a company had to decide as a matter of priority whether its product was functional or innovative. If it was sold from grocery stores and petrol stations, it was probably functional with a long life-cycle; and it probably faced a lot of competition. Some products crossed the line between functional and innovative, such as Ben & Jerry’s ice cream in designer flavours, or car seat manufacturer Century Products, which introduced bold fabrics into child seats.

Most of these latter hybrid products, concluded Fisher, had short life-cycles of only a few months because copycat producers were quick to copy and invaded their market.

A genuinely innovative product of the time was the IBM Thinkpad with its radical new cursor. Here again, IBM’s supply chain let it down. The computer giant was so wrongfooted by the demand for the Thinkpad that it was in short supply for more than a year. Thus, Fisher encouraged companies to think more deeply about their supply chains.

Catastrophes

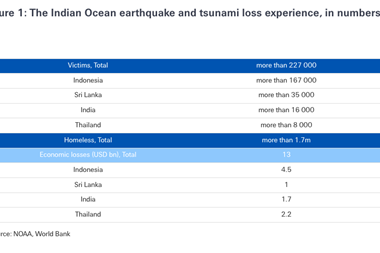

Although new theory propelled supply chain development around the turn of the millennium, a much greater influence has been the series of catastrophic geophysical shocks that exposed the vulnerability of supply chains that not only cross borders but encompass entire geographies.

In different ways, Iceland’s volcanic ash clouds, Japan’s tsunami, Thailand’s floods and the US Superstorm Sandy caused significant disruptions that rippled through the chain up to the customer. In Japan, the automotive industry was particularly badly affected as one supplier after another became incapacitated or weakened by the knock-on effects of the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Each of these events had differing effects. Combined, they illustrated a frightening fact for risk managers: that the capacity of the weather to destroy some or all the links in supply chains had been greatly underestimated. As a result, only the best-managed companies were able to extricate themselves without significant loss.

Of all these catastrophes, it was probably the floods in Thailand that more than any other event shook up existing thinking about the modern supply chain. In 2011, 65 of the country’s 77 provinces were swamped in the worst flooding in more than 50 years. As well as causing death and misery, this geographically localised event brought havoc to thousands of companies that depended on the output of factories that were now under water. Total economic losses exceeded $45bn and insurable losses quickly mounted to more than $15bn. The worst-affected companies were those with a physical presence in Thailand in terms of factories and inventory – thousands of Honda’s vehicles, for example, were covered by 4m of water.

It was an unprecedented supply chain disaster. According to the best estimates of Thailand’s Department of Industrial Works, at least 7,510 industrial and manufacturing plants were destroyed, damaged or affected. Global product shortages occurred in industries as diverse as electrical appliances, medical equipment, automotive and, in particular, computers.

As US accountancy firm AdviseNet has pointed out: “If lessons are to be learnt, these catastrophes point to the need to build resiliency into supply chains as a business priority. Companies should look long and hard at their operating models and develop strategies that result in supply chains that are stable, efficient and able to respond quickly in the event of a disruption”.

This is exactly what multinationals, large and small, have been doing ever since. They have been building redundancy into their supply chains. If a supplier suddenly is unable to supply goods, they have (or should have) stockpiles or alternative suppliers on which to fall back.

Catastrophe plus

As supply chain specialists point out, companies embrace the entire spectrum of a country’s risk when they engage suppliers outside their home base. These include political, legal and financial systems.

That realisation was underlined by the series of natural catastrophes. However, it is clear that the company at the head of the supply chain ends up assuming a heavier burden of responsibility throughout the chain that may be unconnected with catastrophe. Retail giant Walmart, for example, has spent the past five years on a global project to reduce its suppliers’ packaging waste by 5%. Although 5% may not sound much, it saved some $12bn across all suppliers ($3.4bn for Walmart alone) and 252.49 million litres of fuel a year.

As chief executive H Lee Scott said at the time, in a telling insight into modern supply chain management: “Even small changes to packaging have a significant ripple effect. Improved packaging means less waste, fewer materials used and savings in transportation, manufacturing, shipping and storage.”

Geopolitical

Although industries such as shipping have always faced disruption in many forms, the latent dangers in offshore production by all kinds of companies have surprised many, not least in the vast SME category. The incipient civil war in Ukraine is a geopolitical threat being felt across Europe, by industries as diverse as aviation, tourism, automotive and steel.

More lessons remain to be learnt. As Robert Kuchinski – New York-based director of AIG’s vendor and business partner services – points out, the modern supply chain is a recent phenomenon with which risk managers are only just coming to terms.

“The reality of supply chains is that about every supplier is somebody else’s customer – vulnerabilities exist on both sides of the chain,” he explains. “Damage to a supplier can delay production and cause a ripple effect for organisations relying on the product.”

Much remains to be learnt about how to prevent – or at least mitigate – the ripple effect.

No comments yet