An overabundance of eco-labels and soft testing criteria is making it hard to consume responsibly. Are these green seals losing their clout? Nathan Skinner investigates

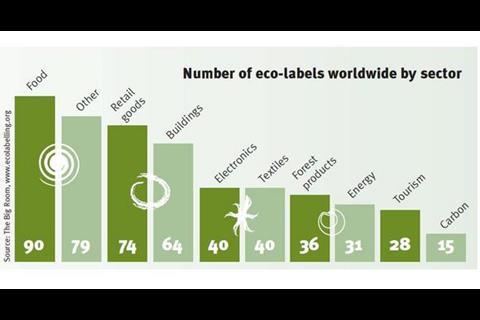

Are there just too many eco-labels? Well, if you think nearly 500 worldwide is too many, then the answers is ‘yes’. An incredible number have flooded shop shelves in the past few years. It’s easy to understand why companies like them.

Research show that environmentally conscious consumers are much more likely to choose a product if it’s been stamped with a recognizable eco-label. Each one is designed to help consumers make a responsible choice.

An eco-labelled product is supposed to fulfil some strict environmental or social criteria. The problem is consumers are losing faith in these so called badges of honour. There’s no easy way to distinguish between honest intent and greenwashing.

Partly this is because there are so many eco-labels, it’s impossible to tell which ones are the best. Is organic coffee better than Fairtrade tea? Is wood from a Forest Stewardship Council forest better than the Sustainable Forest Initiative? And how does a consumer know that if something has an eco-label, it actually meets the standard? Closer scrutiny has shown that some just don’t stand up.

Eco-labels have been available to consumers since the 1970s but in recent years, interest in labels on consumer products has increased substantially. Big Room, which specialises in eco-labelling oversight, has identified nearly 500,000 products, in almost every sector, that have a green label or certificate. The majority of existing eco-labels are in food and other consumer retail goods, and they tend to be concentrated in Western Europe and North America.

Worth the paper it’s written on?

A report released by forest stewards Fern discovered that illegally harvested wood had found its way into paper given the European Ecolabel, which is intended to be awarded for environmental excellence. The report revealed that operations by Indonesian paper-producers Pindo Deli have had a devastating impact on Sumatran rainforests, causing deforestation, harming indigenous people’s livelihoods and threatening endangered species such as the orang-utan.

Pindo Deli is part of the controversial Asian Pulp and Paper company, which has been criticised by environmental groups. Lukas Hammer, eco-label coordinator at the European Environmental Bureau says: “Unfortunately, this comes as little surprise.

We have been warning that stricter requirements on the origin of forest-related products were needed to avoid having wood from highly controversial sources in eco-labelled products.”

The problem is that most certification systems aren’t regulated at all. To get a European eco-label, companies must prove they have obeyed a set of ecological criteria established by the EU, which should guarantee that only the most environmentally friendly products on the market are awarded the label. Environmental groups say the requirements aren’t strict enough.

Affectionately known as the ‘EU flower’, this ecolabel is a voluntary scheme aimed at making it easier for consumers to buy green. The label was established back in 1992 and by 2009 it had been awarded to 3,000 products. The eco-label’s website claims products carrying the EU’s approval must meet strict targets, stating: “While the logo may be simple, the environmental criteria behind it are tough.”

The EU eco-label for paper is meant to reassure consumers that the pulpwood used to make the paper comes from sustainably managed forests. The eco-label assures customers that “only the very best products, which are kindest to the environment, are entitled to carry the EU eco-label”. But Fern’s report claims that two brands of Pindo Deli paper, Golden Plus and Lucky Boss, do not deserve the accolade.

The raw material used to manufacture Pindo Deli’s paper comes from two pulp mills in Sumatra, Indah Kiat and Lontar Papyrus, according to Fern. The mills were designed to use rainforest timber as raw material until a large enough area had been cleared to establish industrial tree plantations to feed the mills, it said.

“The forestry operations that supply raw material to the pulp mills that supply Pindo Deli are socially and environmentally destructive and some of their operations may even be illegal,” alleges the report.

Furthermore the research damns the EU’s ecolabel criteria, calling it “very weak” and saying it gives no guarantee that the labelled products come from well-managed forests. The environmental group also claims that the labelling process is opaque. The report shows that there is too little publicly available information to allow consumers to check that the eco-label stacks up.

That ring of confidence

Europe is not the only place hit by the eco-labelling scam. The US Department of Energy (DoE) recently concluded in an internal audit that it does not properly track whether manufacturers that give their appliances the Energy Star label have met the required energy-efficiency criteria, according to the New York Times. Some manufacturers could be putting the stickers on unqualified products, according to the audit.

The Energy Star programme is a government initiative designed to reduce the waste of energy and curb greenhouse gas emissions. Obama has pledged $300m (€245m) of rebates for consumers who buy Energy Star products, so the labels are a valuable commodity, particularly for manufacturers wishing to target consumers interested in saving money and reducing their environmental impact.

But Environment Agency inspectors claimed the Energy Star ratings were “not accurate or verifiable” because of weak oversight. These shortcomings “could reduce consumer confidence in the integrity of the Energy Star label”, according to the audit.

Furthermore, tests carried out by the Consumer Reports magazine in October 2008 showed that some models of refrigerator that carried the Energy Star label did not meet the energy-saving standards.

The tests found that two models of refrigerator consumed more energy than allowed under the Energy Star rating. The main reason for this, it found, was that their tests were tougher than those of the DoE, which issues the seal of approval. The DoE tests were carried out with the refrigerators’ icemakers switched off, but this does not reflect real-life energy use, claimed Consumer Reports.

If the criteria for eco-labelling a product are too soft, then the labels become meaningless. Not only does this make it hard to consume responsibly but it’s also tougher for companies with honest intent to market their products. The criteria for eco-labels needs to be revised and the most egregious offenders should be excluded.

One way to improve standards would be to make the award process more transparent so outside observers can understand the basis on which the labels are awarded. Some eco-labels do this better than others. Certain programmes, such as the Forest Stewardship Council or EcoLogo, require independent verification of a manufacturer‘s green claims. Many others don’t, due to a lack of resources. If the situation doesn’t change and eco-seals continue to proliferate, so will the doubts.