A new report by the Swiss Re Institute outlines the key lessons risk managers and governments must learn from the world’s most deadly tsunami

On 26 December 2004, the world’s third-most powerful earthquake on record (Mw 9.1) struck in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Sumatra, triggering the deadliest tsunami in recorded history.

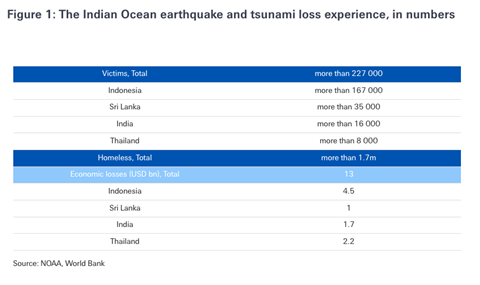

Its waves reached the eastern coast of Africa, 4500km away, leaving a trail of destruction in 14 countries, more than 227,000 people dead, and 1.7 million-plus homeless.

Around 70% of the total USD 13 billion economic losses were in low-lying coastal regions, mostly in Indonesia but also in Thailand, Sri Lanka and India. Debris-laden waves were the cause of most deaths and damage.

Chandan Banerjee, Natural Catastrophe Economist, Swiss Re Institute said: “The Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 claimed more than 227,000 lives. The USD 13 billion of losses were mostly uninsured. We estimates that Indonesia’s economic losses of USD 4.5 billion in 2004 would equate to USD 20 billion in current value based on the country’s GDP growth and inflation since then.

”This scale of loss highlights the need for better tsunami risk preparedness, from warning systems to higher sea defenses and more advanced hazard assessments of potential future events. Fast-rising coastal populations and exposures imply that more action will be needed to narrow protection gaps.”

Improvements don’t go far enough

The Indian Ocean tsunami awakened the region to the devastating loss potential of tsunamis, and the vulnerability of its communities.

The scale of the disaster was unprecedented. The closest coast, of northern Sumatra, was pounded by waves 51m high and was flooded to 5km inland.

The event led to significant advances in tsunami detection and warning, with the establishment of an Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System in 2005 that should help to save many lives.

However, the Swiss Re Institute warns that rising populations and asset wealth in the coastal areas of many fast-growing countries with Indian Ocean shorelines could generate far higher economic losses today.

Banjeree says: “As was the case 20 years ago, with still-limited insurance penetration in the affected areas, the protection gap will still be high. Preparedness for evacuation has improved. Yet countries’ capacity to cope with major tsunamis remains limited and untested.”

For instance, the earthquake in Sulawesi, Indonesia in 2018 (Mw 7.5) damaged tsunami sensors and destroyed telecoms networks, which led to delays and errors in issuing warnings.

In addition, the level of understanding among local populations on what to do in the event of a tsunami is an unknown. In Japan, for example, a warning was issued three minutes after the 2011 ocean earthquake but the resulting tsunami nevertheless still claimed more than 18,500 lives.

Banjeree says: “Across the wide expanse of the Indian Ocean itself, coastal exposures continue to rise. For instance, in India’s megacity Chennai, whose entire coastline was inundated by the 2004 tsunami, the population has grown by 70% since. In Phuket in Thailand, the population has increased by a still more staggering 180%, due to its development as a major tourist destination.”

Preparing for what lies ahead

The Swiss Re Institute says it is not known when this region may next face another tsunami of the 2004 magnitude. However, it warns that the accumulation of populations and assets in these areas point to the potential for large losses and so a need for more robust risk reduction measures.

For instance, after Japan’s disaster in 2011, the height of seawalls there was raised to strengthen risk readiness. But many coastal communities of the Indian Ocean still lack adequate sea defences.

And many of the region’s emerging economies are growing rapidly with often unplanned development that outpaces efforts to reduce vulnerability.

Banjaree says: “More investment in ex ante risk reduction measures, such as restrictions on building in high hazard regions, strengthening and enforcing construction standards for new buildings, seismic retrofitting existing ones and, crucially, raising public awareness, is needed.”

Swiss Re says that insurance can be a key pillar of support as a source of investment capital for the building of resilient and sustainable infrastructure to lower the risk.

It adds that through research and modelling activities, insurers also promote probabilistic earthquake and tsunami hazard assessments in each location. This can reduce uncertainties around expected losses, particularly for very low frequency extreme events.

Insurance also provides a timely source of financing for reconstruction, reducing costs to the public sector in covering uninsured losses, and can play a vital role in increasing risk awareness.

However, Banjaree warns that insurance penetration in many of these countries is low. For example, in Indonesia, only about 6% of expected annual economic losses from earthquakes are covered by insurance.

He concludes: ”The region’s rapid economic growth and urbanisation and high hazard exposure, call for effective private-public financial management of earthquake risk - and of weather risks too, in the context of rising temperatures.

“Other countries offer a guide, such as Turkey’s Catastrophe Insurance Pool, a government-insurance sector safety net established after the major earthquake in 1999. Today the pool covers 60% of residential buildings on registered urban land, up from 5% in 2000, and has significantly raised public awareness of earthquake risk.”

No comments yet