The events that dominated the headlines earlier this year show that it is not enough for organisations to predict such occurrences – they have to develop a strategy that plans for the full unfolding consequences

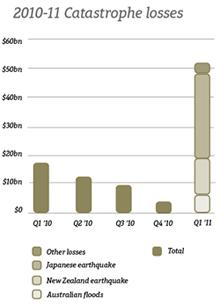

Australian flood, New Zealand earthquake, Japanese earthquake and tsunami, US tornadoes – all of these hit the headlines in the first half of 2011.

Risk Management Solutions chief research officer and executive vice-president Robert Muir-Wood says: “It’s certainly been a bad first half of the year and first quarter in particular. The last two or three years have been very light in terms of natural catastrophes, so maybe we had forgotten what the average feels like. It has certainly not been average in the last few months, but was definitely lower than average in the preceding period.”

Muir-Wood lays a lot of the blame for the recent climate-related disasters on La Niña which affects ocean temperature, but earthquakes are a different matter. In New Zealand, there was a linked sequence of earthquakes triggering each other – and he warns that they may not be over yet.

His message for risk managers is that, while such events in themselves are clearly unpredictable, none of the 2011 catastrophes has occurred in places that are really surprising. FM Global vice-president, market and business development Martin Fessey and vice-president of operations and engineering manager Tom Roche echo this view.

Fessey says: “We know Christchurch [in New Zealand] is in a shake zone. The earthquakes were severe but not beyond expectations. Everyone knows the situation in Japan, with an earthquake long overdue, and the tsunami was predictable as well. Similarly, the floods in Australia could have been anticipated.”

While such disasters may be predictable, some of the corollary issues have been less so. Research into building codes and construction techniques is still continuing in earthquake-hit Christchurch to find out why some buildings were not as resistant to damage as expected.

Roche comments that our attempts to tame these events can have limitations. Regarding the floods in Brisbane in January, there are some questions over the operation of the Wivenhove dam. With the dam full, officials had little choice but to make controlled releases of water, increasing the level in the Brisbane River and potentially adding to the flood problems in Queensland’s state capital.

In Japan, the damage to infrastructure was what might have been expected, Roche explains. “Natural catastrophes like earthquakes tend to have an impact on a large area, so damage to roads, public works and utilities can be expected. However, the unexpected element was the impact on the Fukushima nuclear station and the consequences in terms of shutting down some of the power systems and imposing rolling power blackouts.”

Preparing for the worst

The nuclear plant impact may have taken companies by surprise. However, Roche says that organisations planning their strategy to offset the effects of natural disasters need to take account of the fact that many natural catastrophes, such as hurricanes and floods, will be followed by disruption to utilities.

The companies that take this message on board can benefit considerably in terms of both preserving profitability and reputation. Roche cites the example of a US company storing supplies of processed fruit. “Our client anticipated that their power supplies could be disrupted by wind storms and ensured they had emergency power generating equipment at their site. In the event, they were able to save the product from their harvest while their competitors saw all their chilled produce ruined,” he says.

He adds that, in putting such provisions in place, it is important to consider that on-site power generation may not just need to work for hours but for days, or even weeks. “Our client rightly saw that their challenge was not dealing with the power outage – they had already provided for that – but in planning to ensure that they could get enough fuel for their power system to last out the crisis,” he explains.

The key lesson is that companies cannot stop the kind of natural catastrophes that we have seen in 2011, but they can implement measures to make their businesses more resilient.

Another example, cited by Fessey, is the importance of keeping the envelopes of buildings intact if wind storms are likely to be a problem.

“We know that heavy winds can rip parts off buildings and, as a result, rain is driven into the building and causes damage. Companies can put measures in place fairly cheaply to deal with this eventuality.”

Fessey concludes: “We live in a risky world from a natural catastrophe point of view. The prevalence and consequence of such risks are only likely to increase.

“It’s a wake-up call in terms of where companies locate their facilities and supply arrangements – and how they can invest in some quite simple and inexpensive protections that will put them ahead of the competition should disaster strike. SR