Facing up to the eurozone crisis: Banks and taxpayers would need to stump up at least €2 trillion to sort out debt woes

Probably the biggest risk facing European banks and governments at the moment is Greece: years of profligacy have le the Greek state with a huge deficit (roughly €357bn as of October). It is so big it threatens the Eurozone’s survival.

There’s no way Greece can repay that debt on its own: this has spurred other European nations, led by Germany and France, to throw Greece a lifeline, an EU bailout fund of around €500bn.

But even that might not be enough. Risk analysts at Stratfor, a US-based global intelligence c ompany, think Europe needs to stump up at least €2 trillion to sort the problem out. This fund would pay for three things, says Stratfor.

First, roughly €400bn would create a “fire-break” between Greece and the rest of Europe. About €800bn is also needed to prevent a banking meltdown once Greece leaves the Eurozone (bankrupting it by definition). Finally, the fund would need another €800bn to bail out Italy, most in danger after Greece.

Without this safety fund, there’s no way Europe’s leaders can kick Greece out, says Stratfor. And it’s hard to see how European statesmen, particularly in the rich north, are going to convince voters to provide this cash, preoccupied as they are with national interests. A lack of strong cross-border leadership is one reason for all the delays, confusion and uncertainty around the crisis.

Germany’s secondbiggest bank, Commerzbank, and others, warned that France’s and Germany’s impeccable AAA credit ratings could be downgraded because of their support of the Greek economy.

As Exclusive Analysis points out: “The price of rescue is cheaper than the price of failure.” A controlled, orderly default, with banks and governments both paying the price, is Greece’s only option.

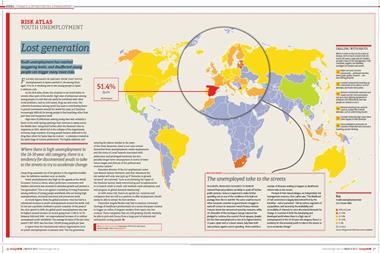

As the streets of Athens have borne witness to the last few months, the economies of southern Europe face enormous social problems as well as financial ones. A broken economy threatens a breakdown in civil order.

Risk Atlas

1. Spain

On 13 October Standard & Poor’s downgraded Spain’s debt rating from AA to AA-. The decision was based on the country’s weak growth prospects and doubts over its financial strength. Further downgrades are expected, as Spain struggles to emerge from nearly two years of recession. The Spanish economy is the fourth largest in the eurozone and is expected to grow about 0.8% this year and 1% next year.

2. USA

The Occupy Wall Street demonstrations in New York City started on September 17th and had spread to over 70 cities by 9 October. The participants are protesting against social and economic inequality and corporate greed, demanding to see steps being taken to ensure the wealthy pay a fairer share of tax on their income and that banks are held accountable for reckless practices.

3. Greece

The Greek debt crisis continued to grow. On 13 June, Standard & Poor’s downgraded Greece’s sovereign debt rating to CCC, the lowest in the world. The European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund on 11 October agreed to release an €8bn loan, part of a €110bn bailout already extended to Greece. The country was hit by a new wave of strikes in October, as the strain of harsh austerity measures led to rising social unrest.

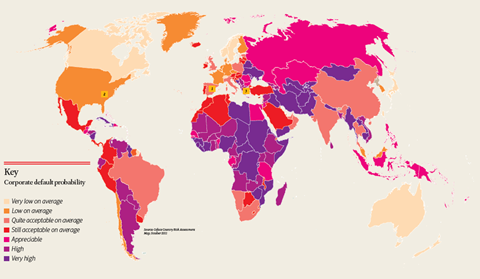

Coface lowers risk assessments

Deteriorating economic and fi nancial conditions led Coface in October to lower the risk assessment on several countries in the eurozone in addition to the USA. The trade credit insurer dropped its risk assessment for Greece by one notch to C and Cyprus to B. The positive watches on A2 risk assessments for Germany,

Austria, Belgium, France and the Netherlands were removed (an indication that the credit risk rating could change soon). The A3 risk assessments for Italy and A4 for Portugal were put under negative watch (indicating that the ratings could be about to deteriorate). Coface also removed the positive watch on the USA’s A2 risk assessment.

EXPERT VIEW

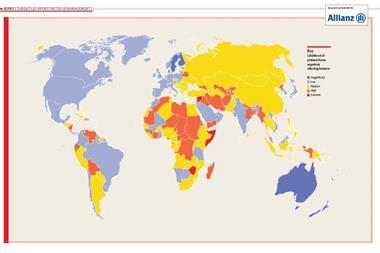

Dr Rolf Schneider is head of macro research at Group Economic Research & Corporate Development, Allianz SE

Keeping ahead of the risk curve

Economic risk pervades every part of our lives. In every decision we take, whether at the personal or business level, economic risk plays a role. Will our business partners be able to pay their bills? Will we able to pay ours? Will exchange rate developments wipe out prospective profits? Will a stock market slump erode our wealth? Will a spike in oil prices make gasoline unaff ordable?

In the shadow of the 2008 financial crisis and haunted by Europe’s ongoing sovereign debt crisis, we have all become acutely aware of economic risk. Will the austerity drives in many countries stoke social unrest and spawn political upheaval? What would be the repercussions of a break-up of the Eurozone, or indeed of moves to closer political union in Europe?

Macroeconomic research attempts to weigh all the risks and, with the help of econometric models and a healthy dose of intuition, feed the results into economic forecasts and scenarios. Any forecast worth its salt contains a listing of the assumptions supporting the base case and an assessment of the risks that could blow the forecast off course.

This entails keeping a close eye on market data worldwide, spotting trends, interpreting the results of third-party research and searching for telltale signs of developments that might affect our global operations. Risks lurk at every turn - what are the strategic implications of changes in consumer and investor behaviour, of new regulations or of shifts in the competitive landscape? To stay ahead of the curve, risks need to be identified, the interconnectedness of the global risk landscape unravelled and probabilities evaluated. In an increasingly complex world, the importance of identifying and understanding economic risks cannot be stressed enough.

No comments yet