Governments, activists, shareholders and consumers are lining up to attack major companies

Customers assaulted by staff on aircraft. Corporate advertising alongside extremist videos on YouTube. Polluting engines masquerading as green technology. Military intelligence-driven profiling amid allegations of manipulation of democratic elections. Oil pipelines, product recalls and tax avoidance. Corporates are under fire – from within and without.

If anti-corporatism, as such views might be broadly labelled, was determined solely by the number and weight of scandals, the past year – and certainly the past ten – could have witnessed the dismantling of not only a handful of banks, but also of multinational interests across the globe.

In reality, that scenario is scarcely more likely than US model and TV personality Kendall Jenner solving world peace by drinking Pepsi. In the last two decades, however, the relationship between corporate agencies – including governments, shareholders and consumers – has changed, and the threats they pose are increasingly apparent and amplified.

EXISTENTIAL

“Multinational corporations face numerous threats to their business by merely having global footprints. The obvious opportunities are shadowed by risks that may very well be existential to a corporation’s viability,” says Michelle Tuveson, executive director at the Cambridge Centre for Risk Studies, Judge Business School at the University of Cambridge.

“I would essentially define anti-corporatism as a collective negative attitude toward for-profit corporations, and the profit-making activities in which they are engaged,” says Paul-Brian McInerney, associate professor of sociology at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

Were it that simple. Paradoxical at best, nebulous at worst, anti-corporatism is a mighty conceptual challenge for risk managers and boardrooms alike. All agree it is nothing new. Attempts to bring it into focus through measurement are increasingly common. But that is largely where consensus ends.

Corporate business has been a lightning rod for popular discontent for hundreds of years, tracing back to the Boston Tea Party in 1773, or even the foundation of the East India company in 1600.

The lifespan of companies in the S&P 500 Index has shrunk from an average tenure of 61 years in 1958 to 18 years today.

Wherever organised business has asserted itself, forces opposing the unbridled pursuit of profit have emerged. Activism is not the only output. As corporates have grown, so too have the implications of their power.

“Before the end of the 20th century, activism looking to change corporate behaviour was targeted at the state, who could in theory devise and enforce laws to curb them,” says Sebastien Mena, senior lecturer in management at Cass Business School in London.

“That changed with globalisation. We realised that multinational corporations had acquired more power than some governments, and could not be regulated by others. Activists then brought the fight directly to corporations so that they changed their behaviour, rather than being coerced by regulation.”

The backlash that intensified after the boycotted World Trade Organisation talks in Seattle in 1999 has been amplified in the past decade by a predatory mass media – itself part of an elaborate corporate machine – and a more scrupulous, organised public exposed to and armed with powerful and ubiquitous digital platforms. First came Google. Then Facebook.

Experts pinpoint 2008 as an anti-corporate watershed: the moment when big business ultimately became too big; or, too big to fail. It is a crucial distinction. More recently, concerns have escalated following a wave of protectionist lurches from western governments, driven by populism and the rejection of an economic hegemony that has increased the gulf between rich and poor, and uncertainty over Chinese trading intentions.

“What’s particularly interesting is the polarisation we’re seeing in large western markets,” Mena says.

“Take the US or Brexit. Trump was adamant to bring jobs back home, and to shut down the Trans-Pacific Partnership [the world’s largest trade deal] so American manufacturing can survive. He’s much more vindictive against foreign corporations who come into the US and steal jobs and markets.”

“Protectionism poses a real risk for many firms, whether it affects supply chains or access to consumers,” adds McInerney. Ironically, despite often being the rhetorical target, large corporates are better equipped than smaller ones to adapt.

“Trade barriers to the US are impacting us,” says Adrian Clements, general manager, operational risk management for steel manufacturer ArcelorMittal. “But as a multinational operator, it also means imports have reduced and therefore competition.”

We are slowly moving from an age of compliance to an age of transparency – as the result of technology, consumer activism and the primacy of ethics.

ANTI-CORPORATISM IS TRENDING

The simplest measurable impact of anti-corporatist behaviour is on revenue and share price, usually driven by product boycotts. Observers agree that sales can be impacted, yet examples are few and do not, for example, include United Airlines [see below]. Similarly, in the majority of cases share prices recover.

Anti-corporatism, however, is broader than the commercial impacts of populism, protectionism and boycotts, and more specific than anti-globalisation. The breaking apart of corporates is not part of a concerted global strategy, even if negative sentiment towards and anti-corporatist policies are on the rise, and longevity is on the decline.

According to a study from Innosight, the lifespan of companies in the S&P 500 Index has shrunk from an average tenure of 61 years in 1958 to 18 years today.

“The ebb and flow of corporate performance is nothing new,” says Tuveson, “but the increased complexity and inter-connectedness of the business landscape make managing the overall risk exposure to a corporation’s enterprise even more challenging.”

Attempts have been made to map and mitigate this landscape, but results have been mixed, not least with regard to viability statements, implemented in the UK by the Financial Reporting Council in 2014.

“The need for viability assessments has created a lot of nervousness in the boardroom,” says Tom Teixeira, managing director of Alvarez & Marsal, a professional services firm based in London. A report from KPMG last year expressed concerns that companies were neither conducting appropriate risk assessments nor communicating their findings adequately.

The more successful attempts to specifically quantify anti-corporatist risk have been tied to reputation. Tuveson says many corporations have programmes and initiatives to improve their risk culture, and that reputation is a major consideration.

“Decisions for a corporation’s operations at a particular location or within a specific jurisdiction require disciplined analysis. The potential risk exposure can be extremely broad and it is difficult to answer questions such as how much risk do certain decisions pose, and what is the value at risk to a corporation’s balance sheet for making certain decisions. Very few corporations are able to quantitatively answer these questions.”

“From the reputational side, the most sensible approach is still qualitative,” Teixeira confirms.

“More generally we can often model elements but the collective impact on the bottom line is much harder to assess. We’re not talking modelling a risk financially to two or three decimal places… its orders of magnitude hundreds of thousands of pounds or tens of millions plus. That’s sufficient for the purpose.”

SEEING THROUGH THE FACADE

In parallel, attempts are being made to improve corporate transparency and trust. Friso Van Der Oord, director of research for The National Association of Corporate Directors, describes the shift.

“In the US we are slowly moving from an age of compliance to an age of transparency – as the result of technology, consumer activism and the primacy of ethics – where corporate (bad) behaviours and practices are almost instantaneously exposed and can severely damage reputation. Corporations can no longer control their reputation. They have to earn it.”

Few commentators are convinced a regulator-led approach can fundamentally alter public and state perception and engagement with the corporate world.

“If you want a decent reputation, you have to earn it step by step, year by year, again and again,” says Christian Hinsch, chief executive of German insurer HDI.

“This question assumes [corporations] are moving toward greater transparency. But I don’t get the sense they are – at least not broadly,” McInerney adds. In any case, transparency alone may not be enough as Carl Leeman, chief risk officer at logistics firm Katoen Natie, observes.

“A year ago, I was in discussion with a group of lawyers who were asking ‘would you still advise a client on tax optimisation? Advice that could be on the edge?’ Some said we will not develop a tax scheme for a company that is too sophisticated any more, because there is too much potential for reputational damage – even though you are perfectly within the legal boundaries. Perception should always be taken into account.”

A somewhat curious distinction can be made between corporations pay tax, and how much they pay their bosses.

“In the US, we have a big debate going on about revising the income tax code,” says McInerney.

”Absent from this is that tax rates on corporations have crept downward for the past 60 years or so. People – at least in the US – have a general distrust of most for-profit corporations, but see them as a necessary evil.”

The impact of anti-corporatism is much clearer when it comes to executive pay.

“It’s a massive issue. I’m not surprised most large corporates don’t want to talk about it – or anticorporatism in general,” a senior source at one of the UK’s largest banks says. “If leaders and entrepreneurs aren’t getting paid what they think they deserve, and are constantly under fire, they’ll go make their money elsewhere.”

Many highly-paid executives are leaving multinational corporations and joining smaller businesses with a view to receiving a windfall upon a future exit.

HDI’s Hinsch agrees and adds that brain drain is also a distinct possibility. “Talking to people on the US coasts, I sense a high degree of frustration. If the protectionist trend carries on it could be detrimental, as agile talent tends to move to other places.”

SHAREHOLDER ACTIVISM

The remuneration question has been driven by one of the fastest growing anti-corporatist forces: shareholder activism. This can be of the institutional, activist or ethical variety. While shareholders are comfortably on the corporate bandwagon, and often improve business viability, these moves nonetheless strike at the heart of corporate control – the executive.

Shareholder activism is a massive issue. I’m not surprised most large corporates don’t want to talk about it – or anticorporatism in general.

“It’s not strictly anti-corporate or anti-globalisation because activist shareholders don’t engage in disruptive protest,” says Mena. “They engage with corporations to try and change what they’re doing. Depending on how you define anti-corporatism, I would rather say it’s a way to work with companies rather than trying to dismantle them.”

“Shareholder activism is now considered a significant risk to companies,” says Teixeira.

“In terms of corporate reporting and risk, there is increasing pressure to publish more information to reassure these kinds of stakeholders.”

Groups of investors are joining forces to gain influence by proxy, under the shroud of anonymity. In some cases, the risks are self-evident – witness the response in the aftermath of the WannaCry cyber attacks.

“Another development we are seeing is security becoming an investor led conversation,” says Nausicaä Delfas, acting chief operating officer at the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK.

“We are seeing the emergence of a number of institutional investors now questioning boards as to how they effectively manage cyber risk, which in turn is driving increased focus in the boardroom.”

Commentators agree that the pattern is broader than cyber-risk alone.

“Shareholder activism will also be a force against protectionism and populism, simply because in large western firms the shareholder structure is incredibly diversified and international,” says Mena. “I find it hard to see for large firms how an international investor can advise the board to only do business in the US or the UK. It will be a force against shutting down borders.”

Corporate sustainability resolutions, or ESG (environmental, social, and governance – which includes executive pay) are also on the rise, and there are profitability implications regardless of approval.

Recent high-profile examples of shareholders revolting against executive pay proposals include Credit Suisse and AstraZeneca. “There has been a surge of non-financial anti-corporatism in the last 20 or so years. Investors are taking a stance on public issues. It’s a huge trend,” Mena adds.

BP and Shell, meanwhile, faced environmental resolutions in 2015 to climate change mitigation strategies. “Even if some of these resolutions are rejected, they put on the agenda topics that were usually not discussed at AGMs.”

There has been a surge of non-financial anti-corporatism in the last 20 or so years. Investors are taking a stance on public issues. It’s a huge trend.

Teixeira cites a major fashion retailer which changed its supply chain to avoid the use of a dye manufacturer with a questionable health, safety and environmental record. Corporates have to evidence this level of commitment, not just talk about it, he says.

FASHIONING AN APPROPRIATE RESPONSE

Indeed, corporates do not exist in an anti-corporatist vacuum. Their response is broad: Operational, strategic, tactical and even philosophical.

“We are not seeing it as ‘anti’ at all. It’s giving us opportunities,” says Clements. “Anti-corporatism makes the corporate think and change. For us, what Donald Trump is doing – from a pure business viewpoint – is great.”

McInerney, among others, are less bullish. “Anticorporatism can be an opportunity for the right kind of organisation, but that organisation would have to do everything right. For most corporations, it’s more of a threat.”

“Corporates are already mitigating a lot of things,” Clements continues. “By natural selection or by M&A, putting all your eggs in one basket is less common. Years ago you had one plant making one product; that changed to have multiple plants making multiple products. The trend now is back to one or two. It’s a compromise.”

JIGSAW PIECES

At operational level, Teixeira says the response to existential risks means that risk management is becoming a function delivered from both top down and not just bottom up as in the past.

Clements also points to cyclical models of decentralisation that increase operational flexibility and local accountability. They can be linked to anticorporatist agency, including protectionism.

“If anti-corporatism means the boss is no longer exposed, then it’s working,” he exclaims.

“The idea of a corporate comes from having a pyramidal structure, with a corporation at the top. Many corporations are actually a matrix. You’ll find different sections have their own office to protect the CEO. When the shit hits the fan, they go to jail, not him or her. The corporate is not responsible.

Anti-corporatism makes the corporate think and change. For us, what Donald Trump is doing – from a pure business viewpoint – is great.

“When you look at a multinational corporation, what do you see? Most people would say a big company. But what you should see isn’t the jigsaw puzzle, but the pieces. You never really see the big picture. That’s part of the mitigation. If the communication is local, everything is local.”

The multinational response to bad press has to increasingly go on the front foot. “You can lobby the government, finance some campaigns, but a third and more proactive way of implementing a world market strategy,” Mena says “is to try to shape the political environment, not just anticipate it, but influence public opinion and awareness.”

It sounds easy enough, but Mena is quick to clarify the limitations. “It’s successful for people who are already convinced – such as with the US travel ban. The rise of populism is showing there is a greater divide than we think in western societies between two groups, perhaps more. I don’t think big corporates are going to change the minds of those who feel left out. These are the people who voted for Trump and for Brexit. It can be successful, but only when you’re preaching to the choir.”

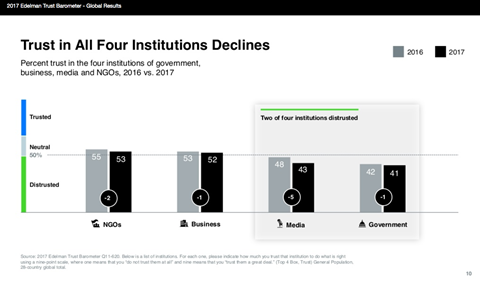

A recent report from Edelman showed that the level of global trust in public institutions (government, business, NGOs and the media) between the ‘informed public’ (60 per cent) and ‘mass population’ (45 per cent) widened to its largest mark since the study began in 2012.

“Corporations are trying to get out in front of the threat of anti-corporatism, either by engaging in prosocial activities, or by making public statements to that effect,” McInerney continues. “This is certainly different than in the past, when such activities were largely reactive. Much of this takes place in CSR departments, but many members of the public are wary of CSR and see it as an attempt to manipulate them.”

STATE OF PLAY

Relations between business and the state still remain the predominant enabler of and check on corporate power. Both recognise the need for mutual support, especially in the prevailing media paradigm.

Corporates have supplemented lobbying as a means of influencing policy by working with trade associations, local government bodies or by creating their own. Hinsch, for example, is chairman of the chamber of commerce for Lower Saxony.

“Businesses are clearly trying to shape how trade regulation will look in the future, working to finance politicians and campaigns that are more open to free trade,” Mena says. “That is slightly different from speaking out against say, a travel ban, because it directly impacts the bottom line.

“We know that government is the number one institution that the public distrusts the most. Big business is number three,” says Mena. [The media is number two]. “Corporations could be more subtle, more targeted, in how they approach this. They must be careful it doesn’t backfire.”

While the vast majority of governments are ostensibly pro-corporate, significant legislation has impeded their growth – most notably anti-monopoly commissions, and Sarbanes-Oxley (2002), a response to the mother of corporate scandals, Enron.

“You need the support from government to do business, otherwise there’s no point investing in a company there,” says Clements. “In Europe, because of strict and moral rules which are extremely anti-industrial or anti-innovation, companies are being forced to go elsewhere.”

“You can sense the frustration of politicians with executives from multinationals,” says Hinsch. “It’s fair to say the relationship between those two parts of the elite has become one of increasing alienation.”

This is in part what drives anti-corporate activism — a loss of faith in the state to sufficiently regulate for-profit corporations.

Another source adds that tensions have been fuelled by the “arrogance of West Coast CEOs” who consider themselves beyond the scope of national legislation.

Clements argues the writing has been on the wall. “I was at a meeting organised by the IRM some years ago. The conclusion was governments are completely out of tune with industry, and industry is way ahead. The gap is getting bigger, and government isn’t closing it: they don’t even know it’s there… the net result was corporations would have to help.”

So, beyond big ticket legislation, is corporate business being limited by the state at all?

“With Trump at the helm, this is not the case as much,” McInerney says. “I think this is in part what drives anti-corporate activism — a loss of faith in the state to sufficiently regulate for-profit corporations. That’s why anti-DAPL [Dakota Access Pipeline] protesters are attacking JP Morgan Chase rather than the state, which approved the construction.”

TRUST ME, I’M A CORPORATION

There are other unintended consequences. McInerney suggests that the public treats corporates and the state as part of the same whole.

“Brexit and Trump’s election are in many ways a rebuke of contemporary institutions, in these specific cases, the state. However, I think the general mistrust in institutions extends to corporations as a class of entities, independent of the state,” he says.

The trend cuts the other way, with corporates also becoming a vehicle for the public to express political outrage. In many cases it is a role corporates, particularly the B2C players, are happy to play. Examples include Apple criticising discriminatory LGBT legislation in Indiana, and PayPal cancelling plans to expand their business in North Carolina for the state passing so-called “bathroom bills.”

“Some corporate CEOs came out strongly against Trump,” says Mena. “What surprises me here is that activists first targeted corporations to get government to react; then targeted corporations directly; and now it’s corporations targeting government to effect change.”

“CEOs often have the ear of the press, so they can write op-eds and other opinion pieces. They can also publicise their pro-social activities,” says McInerney.

The line here is fine and could result in accusations of “greenwashing”: engaging in pro-social activities to direct attention away from anti-social ones.

Big corporate advertising messaging has followed suit. During this year’s Superbowl, commercials championed diversity and inclusivity in defiance of Trump’s travel ban.

In stark contrast to the disastrous Pepsi ad, Heineken also recently released its own that positions the brand more simply as a subtle enabler of connection and consensus between people with otherwise irreconcilable views. It proves corporates can engage meaningfully in politics, there being commercial and reputational advantage in storytelling that builds community in a world increasingly defined by conflict. This trend has taken place in the last three to four years, observers say.

Ultimately, the relationship between corporates, the state and the public can perhaps best be expressed as a triangle, with effort and influence flowing between all three, in both directions, and across national boundaries.

“Consumers have a love-hate relationship with the corporate world. A lot changed in 2008,” says Leeman. “People now have a stronger relationship with brands. In some ways, they are becoming increasingly attached to them. On the one hand they believe in brands, but equally they will go out on the streets to protest against the corporate world.”

RISK MANAGER ROLE

Tasked with swinging this inter-connected, double-edged, anti-corporate sword, what is the role of the risk manager?

Brexit caught corporations by surprise. It wasn’t stress tested. Protectionism is also absolutely on the agenda – and it’s driven by the board.

Cambridge’s Tuveson says progress is needed. “The corporations we have interviewed convey that risk frameworks can serve to anchor their processes for making important strategic and operational decisions. A normalised view of these risks will allow corporations to take proactive measures and improve global corporate governance so that greater fairness is achieved across jurisdictions.”

The robustness of the risk management framework is of great interest to activist shareholders, which means the risk management function is gaining more traction.

“There is a clear opportunity to create horizon scanning mechanisms,” adds Teixeira.

“Brexit caught corporations by surprise. It wasn’t stress tested. Protectionism is also absolutely on the agenda – and it’s driven by the board.”

With impetus coming from the top, bottom and outside, plus the need for specialist skillsets, happy days are surely ahead for risk managers.

“Actually, I’m seeing the opposite,” Teixeira says. “Because of cost pressures on businesses, risk management and compliance functions are increasingly being squeezed to streamline and remove cost.”

The organisational trend is to combine risk management with business continuity, resulting in a business resilience function.

SCANNING THE HORIZON

How corporates adapt to the existential threat of anti-corporatism depends, to an extent, on priorities. Experts conclude there are more pressing challenges.

“I don’t see anti-corporatism as a top 50 risk. Definitely not top 10,” says Clements. “We have others. Education. Sourcing. Artificial Intelligence. We’ll have a workforce with less experience because they don’t work the same job for 40 years.”

“Is anti-corporatism life threatening? No.” Leeman adds. “Is it an issue? Yes, and we’re taking it into account. The statute under which we hire people is under pressure. We are confronted by people who say they’re not making enough money.”

In a world where populism could continue to flourish, the pendulum is as likely to swing back to towards free trade as it is to protectionism. Commentators, including Mena, also expect a corporate backlash.

“Trump is going to get a lot of pushback from corporate interests who want to do business outside the US,” he says. The West may become more protectionist, but not to an extreme degree; I think China will be pushing for more free trade, or at least to open borders to some extent.”

More significant, especially over the long term, could be consumer relationships with big brands, and a continued erosion of their power base driven by new expectations and consumption habits; the media, in particular social; increased activism, including hacktivism, and anti-mega-corporation legislation in certain industries.

At the same time, in line with wider technology trends that will see risk management move from an actuarial to a machine learning, or a dynamic model approach, corporates will increasingly exploit opportunities to respond to existential threats.

What seems clearest of all, despite increasingly disruptive knowns, is that anti-corporatism, even if it is growing in a meaningful way, will not spell the end of the multinational corporation.

Consumers have a love-hate relationship with the corporate world. On the one hand they believe in brands, but equally they will go out on the streets to protest against them.

Clements offers a prudent example of the shape of future big business. “Who owns the cloud? It’s going to be one or two big companies.”

Instead, the convergence of multinational interests with those of the state, transparency (by choice or coercion), accountability (both perceived and real) and the possible resurgence of a new mittelstand (privately-owned medium-sized businesses) in some western economies, means that corporate power will continue to adjust, spread and embed. If global capitalism remains the prevailing economic modality, the multinational corporation will flourish – even if its wings are clipped and the flock loses a few of its number along the way.

CRAFTY CORPORATISM

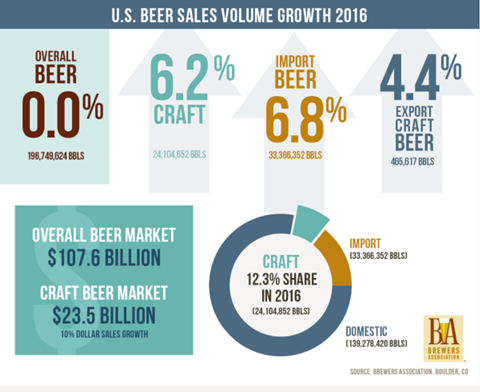

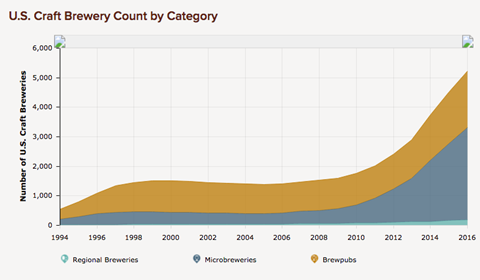

Anti-corporatism can also be driven by corporates. The emergence of the craft brewer in the past 25 years offers a compelling blueprint.

“Their activism is not so much against corporations or even the corporate form – most are incorporated as LLCs – but against corporatism and what it means for their industry,” says Paul-Brian McInerney from the University of Illinois, Chicago.

Craft brewers, he says, are “a taste movement that also works as a market,” balancing the institutional demands of being true to the artisanal mission, but generating sufficient profit “to keep the lights on and the investors happy”.

Management theory generally states that companies with smaller market share but greater specialisation can generate the highest profit margins. But in this case there is a difference. “Craft brewers as a class engage in activities akin to social movements, and their growth has followed similar processes. They organise collectively, share resources and innovate cooperatively.”

US craft beer market share tripled from 2012-16, and accounts for 22 per cent of the US $108bn national beer market. Global micro-brewery sales growth is expected to outstrip the rest of the market by 50 per cent between 2015-20. The trend echoes across consumer packaged goods (CPG) segments. Large CPG brands in the US lost 3 per cent market share from 2011-15.

The typical corporate response is to buy growth. Around 25 per cent of craft breweries are already controlled by a corporate, although their branding is usually maintained.

In the 21st century brand loyalty has evolved, and cannot be easily bought with a punchline. Consumers are increasingly influenced by product quality, brand commitment and engagement – not the traditional levers of price, convenience and familiarity.

As David Beisel, Co-Founder at NextView Ventures, wrote for CB Insights: “If you want to win in a maturing industry, you need to be either a Budweiser or a laser-focused craft brewer.”

TAKING STOCK: THE PRICE OF SCANDAL

Bigger corporations are subject to the most scrutiny. They have the most to gain, but also the most to lose. “They are also more likely to be targeted by activists of any stripe because it generates publicity, which is damaging for the target and enhances the reputation of the activist,” says Paul-Brian McInerney.

Studies by Kellogg University’s Brayden King from 1990-2005 showed companies which suffer product boycotts experience stock declines of almost one per cent per day of national print media coverage. A quarter of boycotts resulted in “a concession from the target company”. In the age of social media, which highlights and amplifies corporate misbehaviour, there is little reason to think this will have changed.

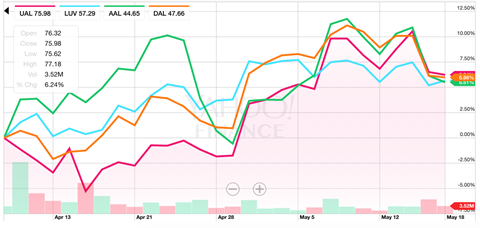

On the other hand, stocks recover – and usually, fast. After United Airlines forcibly ejected a passenger on 10 April this year, causing almost unprecedented consumer backlash, the stock bounced back from a 4 per cent fall within a week after the company reported strong first quarter revenue and earnings. It also revised its expected 2017 passenger growth up from 1-2 to 2.5-3.5 per cent, suggesting the boycott would have limited material impact. United Continental’s share price has since risen to its highest mark in history. No such thing as bad publicity, then? Not quite.

The King thesis of a one per cent per day decline could still hold true, but it does not (and is not designed to) account for other influences including United having little competition on a number of its routes. Commentators also note that the bigger reputational impact of the scandal will be on the industry at large. Curiously, since the scandal, the four largest US Airlines – Southwest, Delta, United and American – saw their share prices rise by an almost identical amount: 6 per cent.

“If risk managers aren’t thinking about anti-corporate sentiment, they should be,” McInerney says. “Someone in the investment world is surely looking for opportunities to short the stocks of potential targets.” The day that United experienced its biggest shopping spree in recent history? 10 April.

For context, Volkswagen’s shares fell a third in two days in September 2015 after admitting rigging its emissions equipment, and BP’s shares halved in the two months after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. Neither stock has recovered. The crucial difference, of course, is massive revenue and cost impacts, including fines.

There is some division of opinion of boycott on earnings, not least because attribution is challenging. Commentators highlight Uber’s recent move to exploit a commercial opportunity arising from a taxi strike (its infamous surge pricing model), but it remains unclear whether it had any negative impact on revenue.

No comments yet