In an extract from his book Reputation Economics, Joshua Klein considers how the concept of abundance through technology is changing basic business models

A new twist on an old theme

We’re already trying newer things with our technology than simply copying past efforts. One of the most significant ways in which this is happening is in using technology to reshape commerce from fiat-currency-based (scarcity) to reputation-based (abundance) economies. In the effort to make our existing systems more efficient, we’ve created a bevy of technologies and commercial platforms that are reshaping how commerce is done. It’s completely organic and unplanned, but the emergent effects are starting to shape up to look awfully familiar.

Historically, scarcity ruled our markets. Only so much grain was available in a given field, only so many fish in the river, only so many rugs woven in a season. But the way we exchanged those goods was often oriented around maximising their reach: through gift economies or trade emphasising mutual benefit. Frequently, a limited amount of a particular good was still able to create more value than the sum of its parts.

For the first time, we’re starting to see that same effect happen again. Except this time, it’s because the grain, the fish and the rugs are becoming virtual. Infinitely reproducible, freely and limitlessly distributable. For the first time, the idea of a thing – its design – is enabling us to maximise our return, and to do it in a way that more people benefit from. It’s a new economy – one of abundance.

The Thingiverse and 3D printing

When I say “abundance economy” I don’t mean to infer that the planet has become richer than before. Aside from the occasional meteorite, we have the same materials to work with that we always have – and nowadays we have a lot more people to use them up. Instead, I’m referring to both physical and virtual goods. And in terms of the physical, the biggest change is in hyperlocalised, on-demand physical production and globally distributed designs.

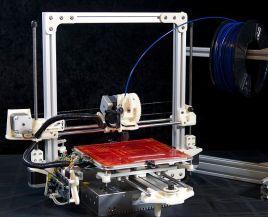

There’s a trend in Brooklyn, New York, where families are buying MakerBots-breadmaker-sized boxes you assemble yourself that use extruded plastic to ‘print’ 3D objects. Why families? Because small, complicated, and unique plastic parts make up 75% of the expensive-to-replace components that break on strollers and children’s toys.

The value in these pieces isn’t in the plastic that comprises them – a few cents of plastic is a few cents of plastic anywhere in the world. But the specific design required is worth quite a bit, and until now that design was owned by the stroller manufacturer, who would often require you buy a whole new stroller to replace it.

Now, however, you can log on to Thingiverse.com – a community-run meritocracy of people who make 3D designs for printing on machines like the MakerBot – and download exactly what you need, usually for free. A few cents of generic plastic thread in your Makerbot, and your stroller is up and running again. Right now, there are more than 32,000 discrete designs on Thingiverse. It’s growing fast, and it’s hugely popular for anyone who has access to a 3D printer.

Keep in mind that the wizards at MakerBot Labs are currently working on printing 3D objects with multiple materials. That means you might be able to ‘print’ a fully functional computer, mobile phone or other device in the near future. For that matter, serious investors are already sinking cash into companies looking to 3D print meat and other foods. In the Netherlands, there’s an architecture firm that’s in the process of printing an entire house.

This shift moves design to the forefront of product development— ahead of manufacture, distribution or anything else. Design as the most significant requirement of a product is an interesting twist, as it’s completely non-physical – and as we’ve noted, non-physical goods are extraordinarily native to the way commerce has evolved on the internet.

A good example is how disrupted the music and movie industries were when their products went from being physical goods (CDs or DVDs) to being non-physical goods (mp3 or AVI files). All of a sudden the markets for these goods shifted completely, moving from the physical, bricks-and-mortar method of selling, shopping and buying movies and music to an online model. Pricing changed. Distribution changed. Advertising changed. All because the good was now non-physical, meaning infinitely reproducible, (almost) freely distributable and completely derivable.

Those features are all now true of most anything in your home as we approach being able to ‘print’ most physical goods. Like a chair you saw in a store? Now you can snap a picture (or series of pictures) of it, import those photos into a computer program and use it to derive a 3D model that you can then tweak, colour, size and then print in a variety of materials. Or you can just ask a web-based platform to try to recognise the chair in the photo and recommend the nearest match from an open-source library of similar chairs – all of which you can also tweak, colour, size and then print, laser cut, etch and have delivered.

In other words, all the ancillary costs that previously limited the production of a physical good – shipping, manufacture, advertising, distribution, sales and more – are now enormously attenuated. Instead, the primary cost of any individual obtaining that new chair is in its design. Once the design exists, it can be edited by anyone, printed anywhere and distributed across a plethora of platforms for free.

That’s a big difference from the primarily scarce resources that underpinned the production of most goods so far in human history. Now, with the abundance economy, the design of the chair is the most valuable attribute of the chair itself. Sure, I’ll pay or trade or friend or follow you if you turn me on to a steady stream of cool things that include chairs (curating), and/or I may pay a premium to have you print my chair instead of printing it myself (production), and of course I’m happy to exchange more value to have it sent to my house preassembled (distribution), but none of those things holds a candle to the value of the initial act of creating the chair in the first place. If you can do that – design chairs that people really want – and do it reliably, you now hold the keys to the real value of those chairs.

That’s because the more I am known as someone who designs badass chairs, the more people will want my designs and the more I can charge for them before they even exist, be that through barter, trade, or finance. Case in point is PrettySmallThings, aka Casey Holgrin. By day, she’s a set designer for Broadway shows, in which she practises the old method of financial exchange. The director explains a set design he wants, and she goes and creates a single design that she then delivers to him in exchange for financial compensation for her time and effort. It’s a pretty standard arrangement.

Except that a couple years ago she started using a Makerbot 3D printer to create the pieces of her designs. Previously, she would have to use exacto knives and cardboard and glue and wax to create a set of tiny Elizabethan chairs, for example. Now, she designs enormously detailed Elizabethan chairs and prints them. That’s cool, and makes her day job more efficient. After all, if she needs six chairs, she can just design and print one six times.

But there’s a side effect to this. She then takes those designs and puts them on Thingiverse under a Creative Commons license that only requires that you provide attribution (give credit to Holgrin) for the design – it’s otherwise ‘free’ to download, remix and distribute. Now, anyone in the world who wants to print out an Elizabethan chair can just download her designs and print them, or pay her a fee and have her print them and ship them.

Completely outside of the revenue of printing and shipping her designs (which I don’t think is her main interest), PrettySmallThings is benefiting terrifically from this arrangement. For a start, she’s getting pretty well known for her work, meaning that if she wanted to do something else related to design, she now has a hell of a reputation to work with. This also means she can ask for more in exchange for doing this work, since she’s got a widespread audience of people who have downloaded and loved her designs and who are willing to vouch for her. And finally, she’s got a load of people who are eager to work with her or have her design things, all of which are raising the value of her time.

In other words, by giving away her designs ‘for free’, she’s accumulating loads of other kinds of value, all of which can result not just in direct trades for things she wants, but can also create opportunities to do or get things she didn’t know she wanted. That’s an abundance economy – by giving something away, everyone gets more than they would have otherwise.

Free is better than (artificially) scarce

Before we get deeper into this primacy of design, let’s step aside for a moment and talk about some of the smoking wrecks on the side of the information superhighway, most notably the previous incarnations of the music and movie businesses. As much as they’re popular firestarters in the ongoing argument about intellectual property, they’re also excellent examples of how big business can miss the boat in handling a changing market. Both were predicated on the idea that information could be exchanged only by physically handing you a physical artefact that had the data stored on it. In large part, that was the case for most of human history – since Gutenberg’s time, large-scale data transmission was generally limited to stacks of thinly pressed wood or skins.

This limitation echoes the problems commerce has always had up until very recently.

Because the scale at which data could be shared was limited to those people you could reach out and touch, efficient means of distribution were at a premium and required copious intermediaries to facilitate the transaction. That’s why it made sense (supposedly) to charge $12 for five cents’ worth of plastic with 11 songs you didn’t want and one song you did want etched on it.

But then the internet came along and the human race discovered what it had known before these limitations of scale appeared. Before we knew there was another village in the next valley, we freely exchanged information with everyone around us with the expectation that we wouldn’t lose the information in the process. A song, once sung, couldn’t be taken back out of the ears of the listener. The only way to derive value from a limitless good like data was through means of exchange such as a gift economy – through increasing abundance, rather than scarcity. Singing your song to many people, and having them sing it to many other people, extended the value via building your reputation.

That’s what the internet did to the movie and music industries. It reminded us all that bits (information) can only endure temporary scarcity through artificial limitation, and that once they’re shared they no longer suffer those limitations. Just because some bits are encoded in a way that computers can read and most people can’t doesn’t erase the fundamental concept of information as free. And so people learned to decode the music their computers heard so they could share them, and found better and more efficient ways to share them, turning the scarcity economy of movies and music (DVDs and CDs) into an abundance economy (mp3s and AVIs and other formats.)

The result has been a huge increase in the money made by the movie industry, despite its absolute best efforts to stuff the genie back into the bottle. In 2012, for the first time in history, total ticket sales exceeded $10.7bn, with 2013 revenue estimated to reach $10.8bn. Note that this record was reached without raising ticket prices. At the same time, the number of movies premiered in 2012 also went up to a record-breaking 655 movies released. Internationally, box office revenues have been growing consecutively for several years – international grosses almost tripled in the past decade from $8.1bn in 2001 to $22.4bn in 2011. This is all apparently due to the increased exposure these movies are getting by being freely shared, resulting in an increased appetite for a premium experience (such as seeing the film in a cinema).

Music is starting to see the same effect, with subscription music services experiencing a revenue increase of 13.5% in 2011 (from $212 to $241m), with paying customers climbing 18% (from 1.5 to 1.8 million), according to the RIAA.

The internet hasn’t dissolved the value of music or movies; it’s only removed the artificial costs of all the middlemen that used to be required for distribution. That means the people who are producing the goods, and those who are consuming them, are all able to benefit directly, because now when I want to check out an artist or preview a movie, I can do so for free, instantly, via the internet.

That’s what happened to an entrenched, thoroughly physical-goods-oriented business ecology. Now imagine what will evolve in its stead as other types of data emerge. We know that what happened to movies and music is also changing ebooks, magazines, newspapers and other forms of media, but what about goods that don’t exist yet? What happens when 3D printers start being able to make food or medicine? What is going to emerge as e-Ink picture frames are able to display any piece of artwork ever made? Or car designs begin to make use of the gigantic third-party aftermarket for swapping home-printed components?

I’ll tell you what happens. We recognise that almost any consumer good is fundamentally recombinable and reproducible, the same way that music always was, and the design again takes primacy as the value over the good itself. One of the side effects of design taking primacy is that the self-same fractalisation of markets that results from allowing global non-financial exchange (that is, each individual in a trade or barter exchange represents a unique set of interests and values, creating a dyadic market for each trade) is that mass-market goods no longer have such great value.

Another embodiment of this was that when laser cutters first became cheap enough for hobbyists and small companies to buy them, a sudden market for engraved laptop cases sprang up. Why? Because customised is always preferable to generic. With 3D printing and abundance economies for design, bespoke is now optional for everyone, meaning that creative expression is an attribute anyone can apply to any physical good. Again, this means the value is in the design, gaining value through distribution and recognition, not through scarcity.

The upshot of all this is an economy in which participation creates more value than it consumes – an abundance economy – and is the opposite of what most of us are familiar with in traditional capitalism – the scarcity economy. If I make cars, I can charge a great deal for each car, because once you buy the car nobody else can. That’s the old model. But if I make the design for a laptop engraving and you use it on your laptop, anybody else can still use that design. In fact, if you use that design, it’s more likely someone else will see it, like it and use it too. The more valuable it is, the more available it is and the greater the net benefit.

That abundance economy explains the rise in everything from YouTube videos to tweets to Reddit posts. It’s why Kahn Academy (a non-profit educational website) is one of the fastest-growing sources of education, why TED videos about astrophysics get passed around among millions, how Thingiverse gets so many design submissions or Etsy has new products posted hourly, or how the Huffington Post has so damn many authors clamouring to write for it.

It’s also why PatientsLikeMe.com, a site where users share their symptoms and treatments, is a better source for R&D than anything Big Pharma could come up with on its own. It’s why people are sending 23andMe.com, a genome-sequencing site, tubes of spit for $100 so they can share their personal physiological data with everyone else.

All of these are instances of people submitting ideas and information freely, to anyone who cares to see them, because they recognise that the more they’re distributed, the more they’re valuable. StackOverflow, that website where technologists compete to provide the best answer to technical questions, is huge because developers know that having a reputation for giving good answers on the site does more than make them look good – it can cement their careers, garner them respect, improve their networks and build their programming ability. That’s not bad for ‘free’.

Even more importantly, all these models are taking off because they represent the most positive aspects of human commerce. Recognition from your peers; the potential for massive, unexpected return on an investment; feelings of belonging and contribution from a global community; and a multitude of avenues for financial and non-financial profit alike are all damn strong motivators.

To put it another way, I can code up a toolkit and patent it, put it on a website and charge people $20 per download for it, and make a small amount of cash until someone writes the equivalent functionality as a derivative product and offers it for sale for less. Or I can open-source license it, distribute it freely, let my community pick it up, enjoy a reputation for writing useful code, potentially get new job offers and have it licensed for big bucks by an industry or organisation I’d never have heard of otherwise.

True, if you put it up for sale there’s still the potential for recognition; the toolkit will still exist, after all. But by making it free, the only disincentive to trying it is if it doesn’t suit someone’s need or interest. This means that the potential audience of people who will take the time to check it out is significantly larger. The important difference lies in the possible return – cash versus reputation. If you have to roll the dice, why not roll for the big return? As reputation economies become larger and more diversified, that big return isn’t in creating scarcity – it’s in leveraging the reputation economy.

Joshua Klein (www.josh.is) is a hacker who now works with major businesses, governments and internet security specialists. He is an expert on new technology, particularly crypto currencies and Big Data and can be heard speaking at major conferences and events around the world. Reputation Economics (www.reputation-economics.com) is published by Palgrave Macmillan and is available from Amazon.

No comments yet