Banks and financial institutions tend to think of operational risk in terms of financial risks associated with their own transactions and operations. This is certainly a necessary part of the scope, but by no means sufficient, and even less so once the array of operational risk exposures of customers is considered.

The enterprise-wide range of operational risk exposures typically experienced by customer organisations arises from such areas as:

- capital projects

- HR/integrity risks

- supply chains

- business continuity

- physical asset protection

- SHE (safety, health, environment)

- credit risk

- fleet risks

- IT

- product liability

- security

- intellectual property

- product and brand counterfeiting

- marketing

- mergers and acquisitions.

These areas of risk are often complex and interlinked, but uncontrolled risks in any one of them can, and do, lead to significant damage to finances including business failure. Two over-riding and critical issues affected by all such operational risks are corporate reputation and brand, both of which take years to build up and perhaps only hours or days to destroy. Share values, market confidence and the willingness of other companies to engage with you all depend on reputation and brand, and ultimately the very survival of the organisation may be challenged. Put more brutally, your customers' operational risks can become their strategic risks - their nemesis.

The lessons from Barings

Most of the official inquiry reports into the Barings collapse in February 1995 focused on financial controls (or lack of them), and the activities of the lone 'rogue trader' Nick Leeson.(1),(2),(3) Very little analysis was devoted to how it was possible for such a person to have been appointed in the first place, promoted and, then allowed and virtually encouraged to undertake his nefarious activities. Human resource risk management (how the thoughts, decisions, attitudes, behaviours, actions, systems and culture within an organisation are marshalled and managed to avoid detriment and enhance beneficial outcomes) was barely mentioned.

Waring & Glendon's study of the Barings collapse,(4) found that four sets of generic factors are prime sources of HR risks, as listed in Table 1. Many of these featured in the Barings collapse. A few examples from Barings illustrate the issues.

Unfavourable contexts

All five unfavourable contexts were evident. Individually they might have been survivable. In combination they proved lethal.

Inadequate HR management systems

Selection and deselection - Nick Leeson had no prior trading experience and was appointed without the checks which would have revealed his lie about an outstanding judgement for bad debt. He was entrusted with major financial responsibilities without adequate checks on his integrity.

Competencies and training - Without any real objective assessment of competencies or training needs, whether on initial appointment or for promotion, it was 'learn as you go'. Qualified back-office staff were scarce. Scepticism, checking and investigation which would have been second nature to qualified and experienced back-office staff were absent and did not impinge upon Leeson's activities.

Promotion and responsibility - How did the unqualified and inexperienced Leeson manage to reach his senior position in such a short time and hold onto it? His promotion appeared to be part of a general pattern that included his superiors.

Supervision and authority - Nick Leeson stated in 1996(5): "... my lines of communication with London were so vague that nobody knew who I reported to ... It was a bizarre structure and one which allowed me to run my own show without anyone interfering."

Reward structures and polices - The scale of bonus-related greed was so staggering that for 1994 bonuses amounted to £84m - more than the declared pre-tax profits of £83m and three to four times the normal level for this kind of banking.

Performance management - Normal forms of performance measurement did not appear to exist. Among senior managers, size of bonus became the working measure of performance.

Inadequate primary task (sub) systems The standard anti-fraud practice of separating front and back-office functions was absent. By virtue of his commanding position over both functions, Leeson was able to inflate apparent trading fees and hide the fiction in a spurious 88888 'error account'.

Human failings

Human error - A high level of errors was normal in the daily records and accounts at Barings Singapore. Trading errors were commonly covered by creating fictitious deals and recording them in error accounts. This was how Leeson got started on his infamous 88888 error account.

Indecision - Two sets of independent auditors (SIMEX and Coopers & Lybrand) reported in January 1995 that there were serious problems, yet Barings failed to act. 'Command and control' decisiveness in the light of changing situations and new information is a vital attribute for senior managers.

Stress Reactions - In the final months before the Barings collapse, Leeson was under such stress that his lifestyle and behaviour degenerated rapidly, with symptoms which should have been spotted and investigated by his superiors. According to Leeson, at that stage he was almost desperate to confess and find a way out.

Deviant behaviour - Leeson became synonymous with the term 'rogue trader'. Spotting rogues is, in fact, quite difficult, as many of their supposed characteristics are shared by others who are decent, competent and law-abiding. The term 'rogue' suggests that only the individual is at fault, whereas, as in Barings, the lack of robust risk management systems (RMS) is clearly a fundamental cause.

Other high profile cases

There are, somewhat depressingly, many high profile cases of large corporations involved in operational risk failures that became strategic risks and have led to spectacular damage, detriment or loss to large numbers of parties and individuals. Such cases stretch back to the 1980s (see Table 2).

Taking the China Aviation Oil collapse as the most recent example, it is instructive that the special investigators commissioned by the Singapore Exchange noted 'serious failures of corporate governance' and found a number of contributing failures uncannily reminiscent of the Barings collapse. These are summarised as:

- lack of effective systems at all levels

- basic back-office safeguards were absent

- the company's trading losses were concealed (in this case by the CEO)

- staff from the CEO downwards lacked the knowledge, understanding and skills required for their respective risk-related responsibilities

- the directors and the audit committee were laissez faire, failed to monitor risk exposures and ignored a specific instruction from the China Securities Regulatory Commission

- an internal culture of secrecy prevented accurate and timely information flow.

Current best practice

Over the last 10 years, spurred by the growing number of financial scandals, various corporate governance initiatives backed by governments and stock exchanges have sought to instill a far more disciplined approach to protecting stakeholders' interests. Prominent examples are the Turnbull code in the UK, the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation in the USA and the Basel II Accord, some being more self-regulatory, more generic and less sectoral and prescriptive than others. Multinationals often elect to adopt common governance requirements across the whole group as far as possible. Risk management is the core of these initiatives. A number of standards and guidance codes are available, for example the Australian/New Zealand, AIRMIC/IRM/ALARM and National Audit Office standards.

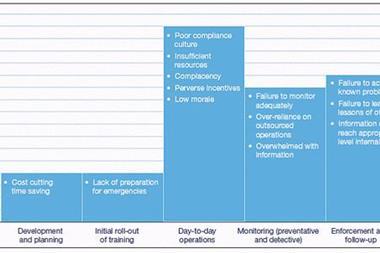

However, there are a number of problems that bedevil risk management today. They include:

- often weak, patchy and fragmented risk management systems, which are poorly integrated across the enterprise

- an organisational risk culture which often reflects departmental silos and dominance by particular interests, rather than the actual risk exposures. Blame is often seen as more important than learning from mistakes. Secrecy hampers learning

- the often narrow scope of independent audits and reviews

- an over-reliance on single measures of risk assessment and performance which may hide hot spots.

Challenges and solutions

Three particular challenges to be faced are:

- how to change the risk culture from one of blame and protection of divisional or professional interests to one of responsible, shared risk-taking

- how to ensure effective RMS integration across the organisation

- how to ensure that RMS are able to cope with the full array of risk exposures and robust enough to ensure that risks are managed effectively and efficiently on a continuing basis.

The solutions to these three challenges are inter-linked. A pragmatic, eclectic approach to RMS design rather than slavishly following one model may be beneficial. There are plenty of models and guidance. Adoption across the organisation of a common RMS model and a common set of internal management standards for the variety of operational risk exposures (for example common accounting requirements, common safety management requirements) then assists in integration. Audit and review results should recommend, where necessary, modification of the RMS design, standards and implementation. RMS integration to common internal standards greatly assists in encouraging, but does not create, a culture of responsible risk-taking. Leadership from the board will be required on a continuing basis.

In conclusion, the enterprise-wide scope of operational risk exposures typically experienced by organisations covers a large array of risk areas that are often complex and interacting. Uncontrolled risks in any one of them can lead to significant damage. To assist in integration of risk management, multinationals often adopt common governance requirements across the whole group, including a common RMS model and a common set of internal management standards for the variety of operational risk exposures. Such integration, coupled with leadership from the board and engagement at all levels, greatly assists in developing a culture of responsible risk-taking.

References:

1) A E Waring and A I Glendon (1998), Managing Risk - Critical Issues for Survival and Success into the 21st Century, Thomson Learning, London 2) Board of Banking Supervision (1995), Report of the Inquiry into the Circumstances of the Collapse of Barings, chairman E.A.J George, 18 July 1995, HMSO, London 3) M L C San and N T N Kuang (1995), Barings Futures (Singapore Pte) Ltd, Investigation Pursuant to Section 231 of the Companies Act (Chapter 50), The Report of the Inspectors Appointed by the Minister of Finance, Michael Lim Choo San and Nicky Tan Ng Kuang, High Commission of Singapore 4) A E Waring (1998), Human Resource Risk Management: Reflections on Barings, Risk Management Bulletin, Vol 3 No 3, October 1998, pp 4-9 5) N Leeson (1996), Rogue Trader, Little Brown, London

This article is based on a presentation at last year's Asian meeting of the Global Association of Risk Professionals.

Dr Alan Waring is chief executive and Steve Tunstall is regional business manager, Asia Risk, E-mail: info@asiarisk.net, www.asiarisk.net