David Nelson, head of climate transition, climate and resilience hub, at WTW explores why a disorderly transition is likely, and the steps risk managers must take to prepare

Limiting the greenhouse gasses responsible for climate change could represent the most significant realignment of the global economy since the industrial revolution.

Efforts will change production processes, supply chains, technology, customer preferences, use of natural resources, as well as costs, prices, employment and asset valuations.

”From a business perspective, it is best to assume the transition is going to be disorderly.”

Some analysts argue that the net impact of a climate-related energy transition on overall global economic growth could be negligible or even positive - albeit with substantial distributional effects between sectors and regions.

These analyses ignore the impact of misaligned action with respect to energy use, supply, and technology, even though uncoordinated action appears increasingly likely.

In fact, from a business perspective, it is best to assume the transition is going to be disorderly.

This should therefore be top of the agenda for risk managers if they are to help minimise the negative effects of a ‘chaotic’ transition.

What is a disorderly transition?

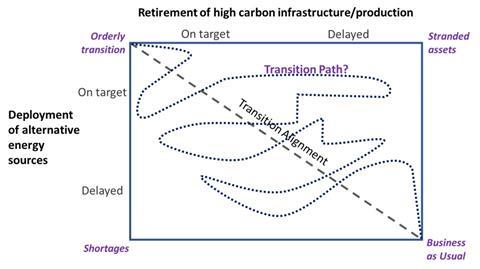

An “orderly transition” to a low-carbon economy would entail a perfect match between the retirement of existing high-carbon assets and the deployment of low-cost, carbon-free replacement resources.

Such a match ensures that throughout the transition the needs of consumers and suppliers are met, avoiding shortages of energy, food or consumer goods and industrial products, while preventing waste from excess supply or unneeded investment.

A disorderly transition, then, is a mismatch that occurs when there are:

- Stranded assets: Where the phase-in of new assets occurs before existing resources and assets are fully amortised.

- Shortages: Where replacement assets are developed and deployed too late to meet market demand to replace the output from the retired assets.

Why we’re on track for a disorderly transition

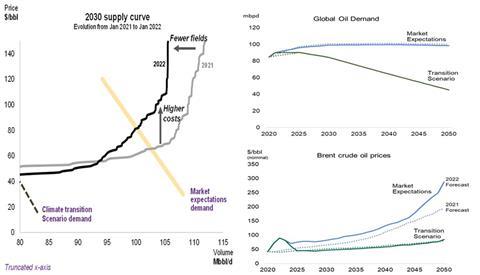

Long-run expectations for oil and coal demand have fallen significantly over the last 20 years.

As a result, oil companies are increasingly reluctant to invest in capital-intensive projects that may take years to produce their first oil and will continue to produce well into the 2040s. The risk of committing large sums is too high.

Instead, they are already shifting investment to shorter term, higher operating cost, lower capital cost investments that produce oil relatively quickly and amortise their investment in a short period of time. These fields are often higher cost, reinforcing the trend to higher commodity price volatility and costs.

Figure 1 shows that the supply curve for potential oil production in 2030 shifted downwards from January 2021 to January 2022, but market expectations for 2030 demand stayed largely static.

Consequently, our forecasts show that without accelerated development of alternative energy supplies and efficiency, energy prices would be between $25 and $30/barrel higher for most of the next two decades.

Figure 1. The impact of falling future oil production on oil supply curves and forecast prices

In other words, a failure to provide sufficient alternatives to oil and other fossil fuels could have a material impact on energy prices.

The extreme volatility and unpredictability of the last two years demonstrate the speed and scale at which markets can change direction and how these changes can completely realign risks in an exceptionally short space of time.

It also shows that it is not only possible to have both stranded assets and shortages simultaneously in adjacent sectors, but it is also to have sectors themselves flip between asset-stranding risk and shortages.

This type of unstable trajectory may be the most likely and realistic path for an energy transition, meandering between shortages and stranded assets and rarely hitting the alignment of retirement and deployment.

Figure 2. A realistic transition path may wander between stranded assets and shortages

The meandering path raises the prospect of an economy that could be simultaneously hit by decreased capital availability from stranded assets as well as higher and more volatile prices from energy shortages.

The uncertainty and costs associated with a wandering, disorderly path could add further economic costs to the transition through both inefficient investment and higher capital costs.

What does a disorderly transition mean for risk managers?

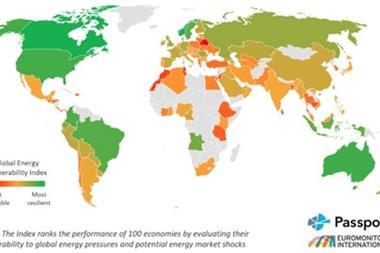

Stranded assets and shortages are likely to occur simultaneously, particularly in different sectors, geographies or timeframes.

The key questions risk managers must ask are: “what is the relative cost of each type of mismatch?” and “what can policy, investment practice or market structure do to avoid the economic consequences?”.

There has traditionally been more focus on stranded assets, but the consequences of shortages from a delayed phasing in of alternatives is becoming increasingly important.

”Companies will need to adapt, or even transform their businesses to become part of the net-zero future and avoid being adversely impacted by it.”

A disorderly transition would impact the ability of organisations to conduct business, causing economic volatility and destabilising the financial system.

Carbon-intensive sectors and their supply chains will be hit hardest.

Transport, agriculture and heavy industries will also be significantly impacted. Like in other industrial revolutions, whole industries may disappear if their business models are incompatible with a net-zero future.

As we enter a new kind of industrial revolution, companies will need to adapt, or even transform their businesses to become part of the net-zero future and avoid being adversely impacted by it.

How risk managers can tackle the threats

The threat of a disorderly transition has far-reaching implications for risk managers, particularly those in natural resource and manufacturing industries that are highly exposed to the transition.

Transition risk management needs to become a core element of long-term strategy.

Companies need to plan and invest for the product demand and supply chains of the future, while maintaining short- and long-term options to adapt to the unexpected directions that the transition will certainly take.

Risk managers would be well served to develop new business development and risk management models that work with customers, consumers, investors, and governments who often face mirror images of the same risks and uncertainty.

The companies that manage these risks will emerge as winners, even while they help reduce the volatility for the global economy.

No comments yet