Xi Jinping’s hugely ambitious One Belt One Road initiative aims to emulate the economic glory days of the ancient Silk Road. Many observers are convinced it will fail. Has he bitten off more than he can chew?

In 2013, Chinese president Xi Jinping launched an epic plan to revive domestic growth and ramp up the country’s position in the world.

One Belt One Road (OBOR) covers about 65% of the global population, more than a third of the world’s GDP and about a quarter of all the goods and services the world moves.

As the name implies, the initiative comes in two parts: the belt and the road.

The ‘belt’ is the physical road from China through Europe to northern Scandinavia. The ‘road’, on the other hand, is actually the maritime Silk Road – essentially, shipping lanes from China to Venice.

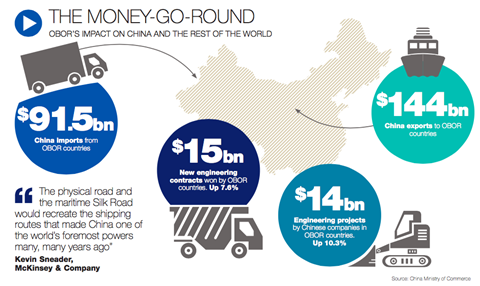

“The belt, the physical road, and the maritime Silk Road would recreate the shipping routes that made China one of the world’s foremost powers many, many years ago,” says McKinsey & Company Asia chairman Kevin Sneader.

The idea, in short, is to redirect China’s excess capacity and capital and export it to Eurasia via these two ‘new’ trading routes.

This will require major infrastructure, trade and investment. Many doubt that the initiative will come to fruition.

But then again, the Chinese and their backers have deep pockets.

BACK TO THE DRAWING BOARD?

China itself has set up a New Silk Road Fund of $40bn to promote private investment along OBOR. In addition, the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) has supported the initiative with some $100bn in lending, while the China Development Bank will invest a similar amount into more than 900 projects across 60 countries to bolster the scheme.

McKinsey & Company managing partner Joe Ngai remains sceptical. “While we have the AIIB and the Silk Road Fund and the New Development Bank, if you add it all together, it’s still a very, very small amount relative to what needs to be funded, which is roughly between $2trn and $3trn per year,” he says. “There’s a lot that’s got to happen before this moves off of the very grand and appropriate drawing board and into practical reality in some countries where it’s proved very difficult to deploy funds.”

Big questions also remain on transparency and the deployment of funds. But for every skeptic there are two optimists and, to date, the funding and political backing for the projects has certainly been impressive.

When it comes to likely beneficiaries, Deloitte Southeast Asia head Dr Ernest Kan – and Xi Jinping, it would seem – have a lot of money on Indonesia.

In April last year, the Chinese government loaned the Indonesian government $50bn to help develop its electrical, mining, energy and railways projects.

“The Indonesian economic growth is very promising,” says Kan. He points out that Joko Widodo, the president since 2014, “has committed to building close to 40 infrastructure projects, including seven railways, six water supply and power, six toll roads, seven sea transportations including sea ports and 12 air transportations, including airports”.

He adds: “By lending money, it could also help [the Chinese] to win some of these foreign construction contracts.”

Observers expect Hong Kong to be a key player too. McKinsey’s Sneader says: “Hong Kong’s role has been the gateway on many levels for China to the rest of the world.

“While that role has been shifting, Hong Kong remains a vitally important financial centre, an RMB trading centre and a source of advice, perspective, and assistance for Chinese companies and Western companies trying to work with each other. So it would be disappointing if Hong Kong somehow didn’t have a very important role to play.”

Western companies looking to capitalise on infrastructure opportunities are likely to encounter hurdles. Dr Kan says that because its purpose is to push out excess Chinese capacity, major projects will largely be undertaken by domestic players.

“In basic infrastructure [the Chinese] deem themselves capable, so there’s probably less opportunities in those areas than the Western companies are looking for,” he says.

They will also need to compete with Japanese and Korean firms that are “very active players in Asia when it comes to infrastructure”. However, Western firms that operate in niche technology fields such as defence and aerospace will be well placed to capitalise. “That’s where [Chinese] technology has been left behind the Western technologies,” he says.

Otherwise, says Kan, Western companies should look for smaller subcontracting opportunities on the larger projects.

But all of these OBOR initiatives depend heavily on political support. “It has to be under a very stable political environment for these projects to continue,” he notes.

And in some countries where leadership changes and political coups are not uncommon, investors and developers alike have voiced concerns.

“If you have a change of government, there may be challenges,” Kan says.

“Just like the nuclear plant project in the UK that was signed between Xi Jinping and David Cameron, the immediate past prime minister of the UK. Theresa May (the new prime minister) seems to take a different view on the nuclear plant project and they want to put it on hold, even though it was approved under the Cameron government.”

SOCIAL CAPITAL

Kan also predicts challenges for local Chinese players, particularly those building projects in countries with differing languages, cultures and risk tolerances.

“The Chinese will have to learn how to build social capital to make sure that they also take care of the local social environment,” he says.

Having sought to maintain a low profile on the global stage for many years, China is jostling for a more prominent position in the international order.

Will Xi Jinping pull off what would surely be his greatest legacy? Only time – and funding – will tell.

No comments yet