Our ability to manage future risks is undoubtedly improved if we can learn from past events and use that learning wisely. No two events will repeat themselves in exactly the same way, but there are often common features of a failure or loss that are relevant to other organisations and societies. By examining these, we can learn valuable lessons that may help prevent similar incidents in the future, or at least enable us to respond more effectively when an adverse event does occur.

This can be helpful when we are looking at a situation, system or product that is gradually undergoing a process of change, but it is of no help whatsoever when faced with something that is completely new and outside existing human experience. Indeed, our thinking can often be hampered by our knowledge and experience of past events. Hindsight is an exact science. But hindsight is no help when trying to predict and manage the technology of the future and the risks it may bring.

Is it all science fiction?

If we try and look into the future, what kind of a world do we see? Will new technology have made our lives better? Will we have found a cure to all our major diseases? Will we be travelling freely in space - replicating food and transporting our bodies from one place to another, at the touch of a button? That was the vision of Gene Roddenberry who wrote the scripts for Star Trek, the television series that first appeared in 1966, several years before man had even landed on the moon.

David A Batchelor, a NASA scientist and author of The Science of Star Trek, attempted to separate the real (or potential) science from the science fiction writers' fantasies. He observed that while some of the fictional technology, such as the spaceship's computer, power generation and impulse engines were within the bounds of the possible, other aspects were nothing more than magic - there to assist the story line, but unlikely ever to come true.

With some foresight, however, Roddenberry said 'The funny thing is that everything is science fiction at one time or another'. What the science fiction writers have done is to give us a vision of what might be possible in the future.

The film I Robot, was based on a series of short stories written by Asimov in the 1940s. In the film, it appears that a robot has overcome one of the universal laws of robotics - that a robot cannot harm a human or allow harm to come to a human - and has killed its inventor. A police investigation reveals a sinister plot which will result in robots taking over the world, and ruling their human masters.

The idea that man might invent a computer or robot that could eventually think and act for itself, is not new. In Arthur C Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey, the on-board computer 'Hal' kills some of the astronauts in order to protect his mission. In I Robot, the writers explore our fears that robotics and nanotechnology might develop independently of human intervention, creating a situation over which we would ultimately have no control.

For other visions of future risk, we could cast our minds back to disaster movies of the '70s, '80s and '90s, such as Towering Inferno, Earthquake, Armageddon, Deep Impact, Twister and Dante's Peak. In Towering Inferno we watched the predicament of a group of people, trapped in a high-rise, burning building. The parallels with the New York World Trade Center attack are sadly apparent. Fire chiefs have admitted that it is almost impossible to rescue people trapped above the level of a fire in a high rise building.

In Earthquake, Twister and Dante's Peak, man is at the mercy of the natural environment, while Armageddon and Deep Impact heightened fears of a major meteor striking earth and wiping out large tracts of the developed world.

More recently, we have been presented with a vision of The Day After Tomorrow, in which our reluctance to control carbon emissions leads to a melting of the polar ice caps, massive weather change, and a fast-freeze of half the planet, resulting in the deaths of millions of people. How much of this is just science fiction and how much is fact?

Current and future risks: the jury is still out

Steven Fink, author of Crisis management: planning for the inevitable, argues that we are constantly surrounded by warning signs that failures and crises are likely to occur. Unfortunately, we are prone to ignore or undervalue the information. Often, we hear only what we want to hear.

'Big Tobacco' argued that smoking was not harmful, long after medical evidence proved conclusively that it was. Even today, the tobacco lobby still argues against damage caused by passive smoking. With the benefit of hindsight, we now better understand the health risks associated with products such as cigarettes, asbestos, silicone breast implants, thalidomide and hormone replacement therapy. So too do the people whose lives were ruined, or cut short, as a result of being exposed to these products.

However, the list of issues where experts currently disagree over the levels of risk is almost endless. Examples include:

- mobile phones and masts

- electricity sub-stations and pylons

- climate change

- MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccination

- ritalin

- genetically modified (GM) foods

- nanotechnology.

When experts disagree, it becomes difficult for the public to make up its mind as to what is, or is not, acceptable risk. An understanding of how the public perceive individual risk issues, and the factors that influence such perception, is an essential component of risk management. For the most part, threats that may impact on the well-being of children are most vigorously opposed. Thus the alleged risks arising from the combined MMR vaccination, proximity to mobile phone masts, or the consumption of GM foodstuffs have gained a lot of publicity in local communities and generated action by well-organised environmental groups.

On the other hand, parents purchase mobile phones for their children, arguing that this keeps them safer, as they can get in touch with them more easily. Yet, the widespread use of mobile phones among young people flies in the face of research which indicates that physical damage may be done to the brain, and in particular to the still-developing brains of children. For the moment, the public seems to perceive the benefits of mobile phones as outweighing any possible risks associated with their use. These views may, however, change as more information reaches the public domain.

Does size matter?

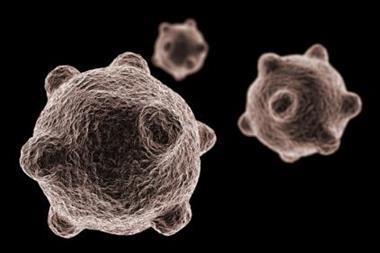

If it is true that we often fear what we cannot see, hear or touch, for example electromagnetic fields, nuclear radiation or virulent disease, then when it comes to nanotechnology we should perhaps be very afraid.

Nanotechnology is a generic term for a large number of applications and products that contain tiny particles, measured in nanometers, which are one thousand millionth of a metre. Although man has constantly sought to reduce the size of products, nanotechnology takes it to new extremes.

In nanotechnology, old laws no longer apply. Electrically insulating substances become conductive; insoluble substances become soluble; nanoparticles can travel almost unhindered throughout the human body. Some have likened the discovery of nanotechnology to a new industrial revolution. Whether this is true or not, there can be no doubt that nanotechnology is big business. The US government has committed $3.7bn to the budget of the National Nanotechnology Initiative for the period 2005-2008, while the EU committed $1.2bn for nanotechnology research in 2003-04.

The name 'nanotechnology' was first used by Dr Eric Drexler in his book Engines of Creation, published in 1986. He also famously coined the phrase 'grey goo' when he mooted the idea that self-replicating assemblers might, if not carefully designed, eat everything around them and create a mass like grey goo that could take over the planet. Needless to say, this idea was later taken up by one of the world's most famous fiction writers, Michael Chrichton, in his novel Prey, which was published in 2003. The storyline is as follows.

In the Nevada desert, an experiment has gone horribly wrong. A cloud of nanoparticles - micro-robots - has escaped from the laboratory. This cloud is self-sustaining and self-replicating. It is intelligent and learns from experience. For all practical purposes, it is alive. It has been programmed as a predator. It is evolving swiftly, becoming more deadly with each passing hour. Every attempt to destroy it has failed. And we are the prey.

Are we in the realms of science fiction again? Or are there some real facts here that we should be concerned about, now, before it is too late.

The Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Engineering in the UK certainly believe that there is an immediate need for further research into certain aspects of nanotechnology. In their joint report - Nanoscience and nanotechnologies: opportunities and uncertainties - published in July 2004, they state that, while such technologies offer many benefits now and in the future, more public debate is needed about their development. Specifically, they see an immediate need for research to address uncertainties about the effects of nanoparticles on health and the environment. Whether introduced involuntarily from the environment, or deliberately as part of a medical procedure, nanoparticles can penetrate all the body's organs, even the brain, and can cross the placenta to a growing foetus.

All of this should give us cause for concern as to current and future health risks associated with such technology, yet products - some of which come into close contact with the body - are already on the market. These include:

- suntan lotion that does not leave a white film on the skin

- more absorbent babies' nappies

- more effective vitamin pills

- clothing that repels sweat and stains.

Those involved in the manufacture of products containing nanoparticles may be even more at risk, as existing PPE (personal protective equipment) is not designed to protect against such tiny substances. Yet, in contrast to debates on the safety of nuclear power or genetic modification, the public does not seem concerned with the threat of nanotechnology. Nonetheless, the media is showing increasing interest in the debate, and even Prince Charles has contributed to the discussion. In an article published in the Independent on Sunday on 11 July 2004, Prince Charles refers to the Royal Society study and writes:

'I am particularly struck by the evidence provided by a recently-retired Professor of Engineering at Cambridge University, Professor John Carroll.

Referring to the thalidomide disaster, he says it 'would be surprising if nanotechnology did not offer similar upsets unless appropriate care and humility is observed'. He ends by pointing out that 'it may not be easy to steer between a Luddite reaction and a capitulation to the brave new technological world, especially when money, jobs and business are at risk'. Those are my sentiments too.'

It has been estimated that only 29% of the UK population are aware of nanotechnology. Currently it is not a major public issue. The question is whether government and business should be adopting the precautionary principle - taking the necessary measures to protect people and the environment at an early stage, even if the the risks have not yet been fully demonstrated.

The final report of the Royal Society/Royal Academy of Engineering suggests that a precautionary approach should be taken. The report states that: 'There is virtually no information available about the effect of nanoparticles on species other than humans, or about how they behave in the air, water or soil, or about their ability to accumulate in food chains. Until more is known about their environmental impact we are keen that the release of nanoparticles and nanotubes to the environment is avoided as far as possible.

'Specifically, we recommend as a precautionary measure that factories and research laboratories treat manufactured nanoparticles and nanotubes as if they were hazardous and reduce them from waste streams and that the use of free nanoparticles in environmental applications such as remediation of groundwater be prohibited.'

The report goes on to recommend that all relevant regulatory bodies should consider whether existing regulations are appropriate to protect humans and the environment, not only with regard to current applications of nanotechnology, but also for those that might occur in the future, and ensure that any regulatory gaps are plugged. While not pursuing the prospect that we may be destroyed by grey goo, or over-run by intelligent nano-robots, it does seem that we are faced with the rapid development of a technology that we do not yet fully understand. There do seem to be strong arguments to err on the side of caution and ensure that in grasping the opportunities that nanotechnology presents, we are also able to manage the risks.

From the very, very small, let us now turn our attention to the very, very big. The designers of aircraft, ships and buildings seem to compete with one another to create the world's largest structures to contain or transport humanity. The Sears Tower in Chicago, constructed in 1974, was listed as the world's tallest building until overtaken in 1998 by the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. In turn, these were overtaken by Taipei 101, completed in Taiwan in 2004. The twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City were ranked 5th and 6th until their destruction on September 11 2001. In their place, the proposed Freedom Tower is expected to rise to 1,776 ft and rank as the world's (next) tallest building, until that too is surpassed, as undoubtedly it will be.

But it is not only buildings where size apparently matters. On January 2004, the world's longest, tallest and widest passenger ship - the Queen Mary 2 - set sail from Southampton. Not to be outdone, the airline industry has weighed in with the largest passenger aircraft so far, the Airbus A380. This two-storey plane has 555 seats and is expected to be 15% to 20% cheaper to operate than the Boeing 747, carry 35% more passengers and have a 10% greater range, making it capable of non-stop journeys of up to 15,000km.

Tallest, longest, heaviest, widest - none of these factors in themselves pose additional risk. A larger ship is not inherently less safe than a smaller one. What does have to be considered, however, is the greater number of people that will be affected should something go wrong. If an Airbus A380 were to crash, the loss of life would be considerably greater than with a Boeing 747. Fire, or a terrorist alert affecting a mega-building would involve the evacuation or rescue of thousands of people. An outbreak of food poisoning or flu on a vessel the size of the QM2 could have a devastating impact in a short space of time. Our safety expectations therefore need to expand to accommodate the enhanced risk that these giant structures present.

Finally, the weather report

2004 has seen some of the most devastating hurricanes in living memory batter the Caribbean islands and the coast of Florida. Bangladesh experienced the worst floods in 50 years. In August, the small Cornish village of Boscastle was nearly washed away when 185mm of rain fell in just five hours. What everyone wants to know is whether such events are part of a global climate change.

According to the UK's Environment Agency, the answer is yes. 2002 was the second warmest year on the planet since records began 150 years ago.

1998 was the warmest, with 1997 and 2001 close behind. All the evidence suggests that the 1990s were the warmest decade in the warmest century of the last millennium. The Environment Agency provides evidence of disappearing glaciers, worsening Mediterranean droughts, unprecedented storms in Latin America and Asia and rising sea levels.

Although there are some natural explanations for climate change, such as solar and volcanic activity, most scientist agree that the gases emitted by burning fossil fuels contribute to the greenhouse effect. This argument has persuaded most of the world's governments to sign up to the Kyoto Protocol and to commit to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. However, the US and Australia have yet to ratify the Protocol, and no formula has been found to include developing nations in the framework.

Are we doing too little too late? Just how far-fetched is the scenario painted in the film The Day After Tomorrow, where climate change is not slow and incremental, but accelerates at an unexpected speed, creating a situation in which governments are no longer in control.

There is no doubt that the time to act is now. Timely action can avert disaster. Otherwise changes will happen - within the lifetime of our children certainly, and possibly within our own - changes so far-reaching in their impact and irreversible in their destructive power that they radically alter human existence. This comment is not based on the words of a Greenpeace or Friends of the Earth activist, but on those of UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, in a speech he gave in London on 15 September 2004.

From a risk perspective, in the short term, we need to consider the location, construction and protection of buildings and other structures. Government, in turn, will need to address the increased likelihood that it will be called on to give emergency assistance when weather-related disasters strike. In the short to medium term, more drastic measures may be necessary to force consumers to change their energy inefficient ways. In the words of Tony Blair, if left unchecked, climate change will result in catastrophic consequences for our world.

The crystal ball

Most of the threats discussed in this article are predictions based on what we currently think we know. The challenge for us all in risk management is to go beyond planning for the inevitable and to 'think the unthinkable'.

Reporting on the al-Qaeda terrorist attacks, the 9/11 Commission found that: 'Across the government, there were failures of imagination, policy, capabilities and management. The most important failure was one of imagination.'

Imagination is the most valuable skill we can bring to the process of identifying and controlling future risks. When you look into the future, what do you see? Will nanotechnology prove to be a blessing or a curse?

Will global climate change result in the destruction of coastal towns and villages? Will the public become increasingly vocal and involved in risk issues? ?

Hindsight may be a wonderful thing, but looking into the future seems to present us with one doomsday scenario after another. Reassuringly, history demonstrates that man is nothing if not resilient and innovative.

If we can use our imagination to create great opportunities, then surely we can also use it in the search for creative solutions to the risks that new technologies and environmental change present.

Dr Lynn T Drennan is executive director, The Cullen Centre for Risk and Governance, Glasgow Caledonian University, E-mail: L.Drennan@gcal.ac.uk

This article is based on a paper presented at the Zurich Global Risk Engineering Forum 2004 in Noordwijk, Netherlands, on 23 September

REFERENCES

Batchelor, D A, (1993) The Science of Star Trek,

Drexler, E, (1987), Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology

Fink, S, (2002) Crisis Management: planning for the inevitable

The Environment Agency: The Royal Society and The Royal Academy of Engineering (2004)