In times of growth, immigration is necessary, but migrants can also be vilified when times are hard

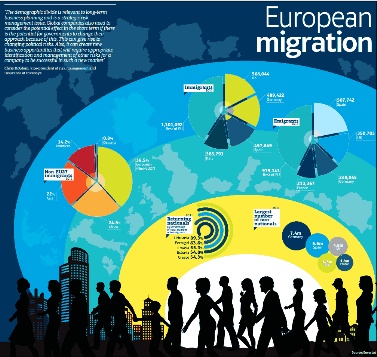

Illegal immigration into the Eu last year fell by 50% compared to 2011. A report released last month by Frontex - the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the EU - revealed that the annual figure last year was 73,000, the first since 2008 it has been below 100,000.

The day the report was released, 11 illegal immigrants trying to reach Europe died after their boat capsized off Morocco. Moroccan authorities claim to have rescued about 6,500 illegal migrants from death at sea in the past five years.

The temptation is obvious - at its narrowest point, only 14km of water separate Africa from Europe. But the Strait of Gibraltar is treacherous and will

continue to claim the lives of desperate people trafficked by unscrupulous gangs.

Frontex says illegal immigration into Europe fell so markedly last year for two key reasons. The ‘Arab Spring’ of 2011 caused a disproportionately heavy influx across the Mediterranean from Libya and Tunisia, which subsequently tailed off. Meanwhile, migrant flows through the Greek-Turkish land border were stemmed by increased efforts by the Greek authorities. Weekly arrivals that once reached 2,000 were reduced to about 10.

A complex and controversial issue

Open borders lie at the heart of the EU and population movement within is continuous. Residents of the 26 countries that signed up to the Schengen agreement do not need passports to travel to another member country.

Migrants move for many reasons, with better job prospects and higher wages the key drivers. For business, migration is essential for growth as it increases the size of the available workforce and the talent pool from which to draw.

In practice, this means a flow of movement from younger EU nations such as the Czech Republic, Poland and Estonia to the richer, more prosperous countries, including Germany, the UK and France.

In times of growth, an increasing workforce is welcome and necessary. Europe’s ageing population and low birth rate also makes it a requirement. At its most basic, migrants do work others are unwilling or lack the skills to do. But migration works only when the migrants work, otherwise they become a burden.

As such, the current economic turmoil in Europe has created a different perception of migration even among tolerant countries. Support for right-wing parties with pro-nationalist or anti-foreigner agendas has increased in recent years in countries such as Denmark, Switzerland, Norway, Belgium and France.

Meanwhile, concerns have arisen among some EU countries about the potential mass influx of Bulgarians and Romanians next year when labour markets have to be open fully to people from those nations that joined the EU in 2007.

The UK government is planning to restrict entitlements to some social benefits. Germany too is fearful, having seen a six-fold increase in migration from Bulgaria and Romania in the past six years.

Germany’s interior minister Hans-Peter Friedrich said recently: “Does freedom of movement mean we have to assume people from all over Europe who believe that they can live better on welfare in Germany than they can in their own countries will come to Germany? This danger cannot be allowed to come true.”

No comments yet