The world is a risky place and economic recession has not helped, says Nathan Skinner

It is a sobering thought to consider that the last time the world experienced a crisis of the scale it now does – after the Wall Street crash of 1929 – what followed was the most destructive war the world had ever seen. With luck, the interconnectedness of today’s societies should prevent the same from happening again. But that is not to say the economic crisis will not trigger a wave of political upheaval around the world.

The banking crisis has ignited discontent with the ruling order in the West, where it started. And now, with rising levels of unemployment and inflation in the developing world, this discontent poses a serious threat to political stability. From the anti-capitalism G20 protests in London to the wave of demonstrations against rising living costs in countries as diverse as Senegal, Egypt, Myanmar, Belgium, Russia and South Africa, violent risks are marching hand in hand with the global slowdown. The bigger the economic shocks the greater the likelihood of social unrest and conflict.

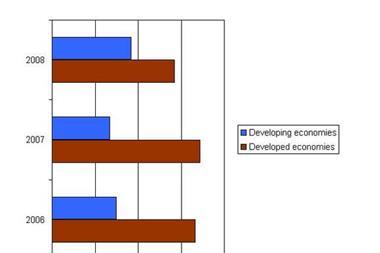

This makes companies uneasy, and they are reconsidering whether to make that investment overseas. The flow of capital into emerging markets is slowing to a trickle. The total volume of capital entering emerging markets in 2009 is expected to drop to $165bn, compared with $466bn in 2008 and the record $929bn in 2007, according to the Institute of International Finance.

By shunning the developing world, companies may be hampering efforts to overcome the crisis, as well as creating problems for themselves. The World Bank estimates that the developing world is facing a financing shortfall of up to $700bn this year. World Bank group president Robert Zoellick, says: ‘Preventing an economic catastrophe in

developing countries is important for global efforts to overcome this crisis. We need investments in safety nets, infrastructure, and small and medium size companies to create jobs and to avoid social and political unrest.’

Faced with the prospect of a deep recession in their home markets some companies are looking for pockets of growth in the emerging world. Emerging market growth rates remain a strong incentive for international investors.

As the balance of power shifts from developed to developing nations, certain leaders of the new world order are shunning foreign investment, preferring to go it alone. Others are actively seeking it. And they face a huge challenge to convince companies that they are a safe place to do business in tough economic times.

The politically riskiest parts of the world are Russia and parts of South America, Africa and the Middle East, according to risk advisor Maplecroft (See map). Charles Mackay, political risk underwriter at Pembroke, thinks political risks are set to intensify. ‘Even prior to the onset of the recession, the general threat of confiscation, expropriation or nationalisation had increased. The economic outlook looks set to accentuate this trend.’

The counter argument is that falling commodity prices reduce the incentive for governments in the developing world to seize assets – because they are worth less. Also, if countries are in a difficult financial position they will not want to alienate the international community, because they may have to approach institutions like the International Monetary Fund for a loan.

Uncertainty is not good for companies who are thinking about investing overseas. So now is a good time to review political risks in some of the world’s emerging markets.

“The politically riskiest parts of the world are Russia and parts of South America, Africa and the Middle East

State perils

China, with its massive domestic market and burgeoning middle class, is one of the first places businesses turn to for an injection of growth. The Chinese state, however, has a say in everything. Earlier this year, Beijing denied Coca-Cola’s generous offer to buy China Huiyuan, the country’s largest juice company. If the deal had gone ahead Coke would have controlled 20% of China’s juice business. The ministry of commerce said Coke’s dominance would have harmed consumers. Denying an outsider a stake in an industry with no obvious national security overtones was a significant move by the communist state. It showed that China is still not willing to completely open its markets to foreign investors.

As a result, despite China’s huge market, other destinations will also be considered by companies seeking new opportunities abroad. Fewer than half (48%) of companies surveyed recently by Atradius intended to focus their efforts primarily on China in the future. Forty five percent said they would focus on India, 25% on Central and Eastern Europe, and 24% on Southeast Asia (excluding China) and Russia. ‘Some companies have realised that multinationals can achieve success much faster in smaller markets such as Thailand, Vietnam or parts of South and Central America,’ said Dr Peter Ingenlath, Atradius’ chief risk officer and vice chairman.

Latin America

Since coming to power in December 1998 Venezuela’s president Hugo Chavez has pursued an aggressive nationalist agenda, mainly funded by oil revenues. Last August, he seized control of Venezuela’s cement industry by taking majority stakes in local units of Lafarge SA and Holcim, and by physically taking over control of Cemex’s plants. Cemex had requested $1.3bn in compensation, ‘a figure well above the actual value,’ said energy Minister Rafael Ramirez. The other two cement companies, France’s Lafarge and Switzerland’s Holcim agreed to transfer control of their companies. But they maintained minority stakes.

Worryingly for international business, Chavez recently won an election victory that could extend his grip on power indefinitely. ‘For international companies, the prospect of Chavez remaining in power past 2012 prolongs the risk of privatisations and expropriation and means the business environment remains unfavourable,’ noted Maplecroft.

Despite his victory Chavez faces a difficult year. He has been able to acquire major sectors of the Venezuelan economy, including energy, power generation, telecommunications, steel and cement production, thanks to high oil revenues. But things are very different now. The price of Venezuelan oil has fallen sharply. Political risk analysts Exclusive Analysis say the drop in oil price will curb Chavez’s nationalist agenda. ‘If oil prices fail to recover in the next two years, the ousting of Chavez by popular vote in 2012 appears increasingly likely,’ they add.

When emerging market states seek larger shares of natural resources, they make life hard for foreign investors. But Robert Amsterdam, a partner in Amsterdam and Perof, says: ‘Foreign investors have rights and recourses that they can and should

vigorously defend and pursue.’

One approach is for multinationals to demonstrate that their goals are in line with the local community. ‘If an investor can structure operations in such a way as to be either economically or politically invaluable to the host government, that may buy considerable protection,’ stresses Amsterdam. Action can also be taken on the international stage. ‘There is a stronger than ever international legal framework for investors, with more and more innovative options to bring disputes into rule of law jurisdictions,’ notes Amsterdam.

“Insurance costs are rising to reflect the enhanced risk landscape.

Ray Antes, senior vice president of AIG UK's political risk division

Resurgent Russia

Another place where state intervention is not uncommon is Russia. The potential for Russia to interfere in the energy sector is well known. It has become an even bigger threat now that the Kremlin has a tendency to flex its political muscles. As a result foreigners are wary of stepping into the energy and natural resource sectors.

The potential for Russian interference was brought into sharp focus late last year when a payment row with Ukraine led it to cut off natural gas supplies to its former satellite state and thus to European consumers, who receive gas through the same pipeline. Russian gas giant Gazprom accused Ukraine of stealing gas and robbing Europeans of about 50 million cubic metres of gas.

An equally worrying trend is Russian military manoeuvres. In early August last year Georgia embarked on an operation to retake the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, an area of Georgia controlled by pro-Russian separatists. Russia launched a furious counter offensive, which resulted in heavy fighting. On 12 April this year, Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili once again condemned the mobilisation of Russia forces in the volatile region. Exclusive Analysis says resumption of large scale hostilities is unlikely.

Protection

However, the military situation is highly volatile and the prospect of escalation, combined with the fact that violence exploded so suddenly in the region has alarmed businesses. Many are now seeking extra protection in the form of political risk insurance. Ascot Underwriting reported that it was receiving more enquiries about the availability of political risk cover as a result of the events in South Ossetia. Julian Barker, senior political risk and terrorism underwriter at Ascot, says: ‘The conflict in Georgia has highlighted how quickly events can alter in this volatile part of the world, a region which is such an important artery for the transit of hydrocarbons.’ Mackay confirms that market conditions have been hardening. He says this trend will continue in 2009. Ray Antes, senior vice president of AIG UK’s political risk division, adds: ‘Insurance costs are rising to reflect the enhanced risk landscape.’ The costliest markets are Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Ukraine and Pakistan, he says. Capacity is also tight in Turkey, Russia and Nigeria.

Terrorism

Outside the trouble spots of Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, terrorism is not normally considered more than a remote risk. But the threat of Islamist terrorism in India was brought to the world’s attention in the November 2008 Mumbai massacre. Several men armed with hand grenades, automatic weapons, and satellite phones landed in a rubber raft on the shores of Mumbai. They scattered to soft targets across the city and launched simultaneous attacks that held India’s financial capital under siege for days and killed more than 170 individuals. The Pakistan-based terrorist organisation Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LT) was found to have backed the militants.

The scale of the attack, the targeting of Westerners and the delayed response of the security forces attracted huge media coverage. In the United States the FBI expressed concern that Al-Qaeda might emulate the attacks. They warned building owners to be on the look out for terrorists adopting similar tactics. In a statement to the House Committee on Homeland Security, deputy assistant director of counter-terrorism, James McJunkin said: ‘The principal lesson from the Mumbai attacks remains that a small number of trained and determined attackers with relatively unsophisticated weapons can do a great deal of damage.’ The terrorist attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team in Lahore which followed, is another example of a low-tech, but high-impact operation, noted McJunkin.

Maoist terror groups are as much a threat to security in India as Islamic extremism. ‘Maoist violence actually affects a greater proportion of the country, representing an equally serious threat to internal security and business interests,’ according to Maplecroft’s India terrorism map. Eva Molyneux, a political risk analyst at Maplecroft, says: ‘Media coverage can skew perceptions of terrorism risk in a country. Smaller terrorist incidents may often go un-reported in international media, despite having potential to disrupt operations, supply chains and affect local communities.’

No comments yet