A political risk insurance report from WTW highlights the decline of consensus on the liberal international order, summarising it as at best, ‘lukewarm’.

Political Risk is on the rise, warns a broker report from WTW, with bilateral investment treaties under strain in a multipolar world.

If the order is indeed in decline, will these changes – from the adoption of the rule of law to trade openness to the protection of intellectual property rights – be reversed?

That is the key question addressed in the first half of 2024 edition of WTW’s ‘Political Risk Index’.

The index analyses patterns in some of the world’s most vulnerable regions, looking at 40 emerging market countries.

The paper, conducted with Oxford Analytica, finds the overall attitude ‘lukewarm’, partly because the order’s institutions are out of sync with the geopolitical and economic shifts of recent years.

“Whatever one’s views on the so-called ‘rules-based international order’ or ‘liberal international order,’ it appears to be on its way out,” said Sam Wilkin, WTW’s director of political risk analytics.

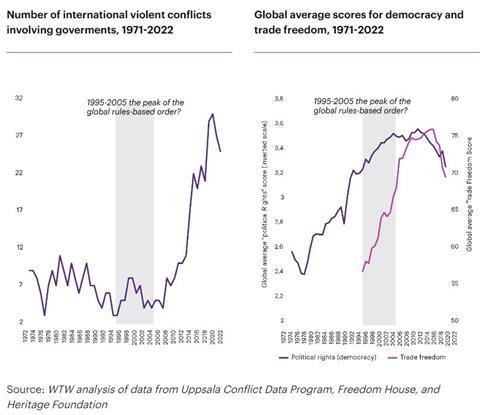

“Macro indicators suggest that the order’s key principles, from international peace to free trade to electoral democracy, are in decline globally,” he continued.

The rules-based order was not based solely in international treaties or indeed the headquarters of multilateral organisations such as the World Trade Organization or International Monetary Fund, he explained.

“Rather, in large part, the order was embedded in the political, legal and regulatory choices of countries worldwide, in many cases via substantial institutional changes, such as democratisation,” Wilkin said.

The importance of bilateral investment treaties, vital for foreign direct investment between counterparties and core to political risk insurance, were highlighted in the report.

For instance, there were more than 1,100 bilateral investment treaties in force worldwide at the late-90s peak, WTW noted.

In 2020, for the first time, the number of bilateral investment treaties terminated exceeded the number of new treaties coming into force, the report highlighted.

By 2022, the ratio of treaties terminated to new treaties was nearly five to one, WTW observed.

The charts below provide further evidence of the weakening of the international order since its highpoint of the 1990s.

40 countries in focus

Chile, Taiwan and Ukraine are examples of strong supporters of the status quo, actively supporting the order, and making little effort to reform it, WTW observed.

Colombia, Cote D’Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and Zambia were described as “committed reformers”, showing active support, but seeking reform.

Argentina, Kazakhstan, Philippines and Vietnam were termed “friendly opportunists”, sometimes supporting the order, but making little effort to reform it.

Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Pakistan were described as “troubled dependents”, sometimes showing support, but this position is contested.

The “friendly critics”, characterised as sometimes supportive and seeking reform, were listed as Mexico, Morocco, Senegal and Tunisia.

WTW described Angola, Bangladesh, Ecuador and Peru as “the troubled democracies”, sometimes supportive of the order.

Regional powers were listed as another category, sometimes lending support, sometimes seeking to reform, with examples cited as Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

Brazil, China, India and South Africa make up “the rising new order”, WTW said, sometimes supportive but “strongly seeking to reform” the system.

Those on the sidelines with no active position meanwhile include Cameroon, Indonesia, Mozambique, Thailand and Uzbekistan.

And at the end of the spectrum, Iran and Russia, as well as Cuba and North Korea, are the “opponents actively opposing the system”.

What does it mean for businesses?

The report notes that businesses also struggle with geopolitical transitions.

Wilkin says: ”The complex institutions of business, from the organisation of corporate functions to the fine print on legal contracts, are closely attuned to the political and geopolitical environment - a point that is usually not obvious until that political environment suddenly changes.”

For example: during the colonial era, legal contracts tended to be well-suited to the harsh strictures of colonialism. If the price of a natural resource went up, foreign investors often enjoyed high levels of profitability.

After World War II, there was a rapid transition from a colonial to a post-colonial world. In some post-colonial revolutions, foreign investors lost everything (Iran, Cuba, China).

As commodity prices spiked in the 1970s, and huge profits went to foreign investors, host governments often gave up on the time-consuming process of renegotiating contracts and leaned into nationalisations.

The report notes that according to some estimates, by the close of the 1970s, nearly a fifth of all foreign investment overseas had been expropriated - including nearly all foreign oil and gas and mining investment in emerging markets, much of which was based on colonial-era legal contracts.

Will the current geopolitical transition be any kinder to globalised business?

Wilkin says: “The rules-based order made the world safe for economic globalisation. Presumably, if globalised companies knew then what they know now (that the order had a shelf life), they might not have distributed their production locations, core markets, and vital functions around the world in the way they are currently distributed.”

He adds that adjusting supply chains to match the decline of the order will probably be easiest approach for many businesses. However, this may prove expensive and time consuming, in part because of unexpected threats, e.g. in the Red Sea.

Developing new key markets and relocating offshored functions will probably be harder, as shareholders tend to react negatively to actions that, in the near term, diminish corporate value.

He cocludes: “In some cases (e.g., Ukraine and Russia) Western companies will linger too long and lose everything. In all cases, making the correct adjustments will require a level of geopolitical foresight that humanity does not possess, our best efforts at model-building notwithstanding.

“It was possible to make money internationally before the rules-based order. It will be possible afterwards. But for many companies, the transition is likely to hurt.”

No comments yet