The rise of machines threatens the jobs of manual workers and professionals alike, and could conceivably lead to widespread civil unrest. But among the experts, not everyone is pessimistic

The idea of machines replacing workforces has been a concern since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, the Luddites notoriously went to the extreme of smashing textile machinery they saw as a threat to their jobs.

When new jobs with better wages and conditions emerged, the fear of machines died away. So, does this imply that the initial concerns about the ‘rise of the robots’ was wrong?

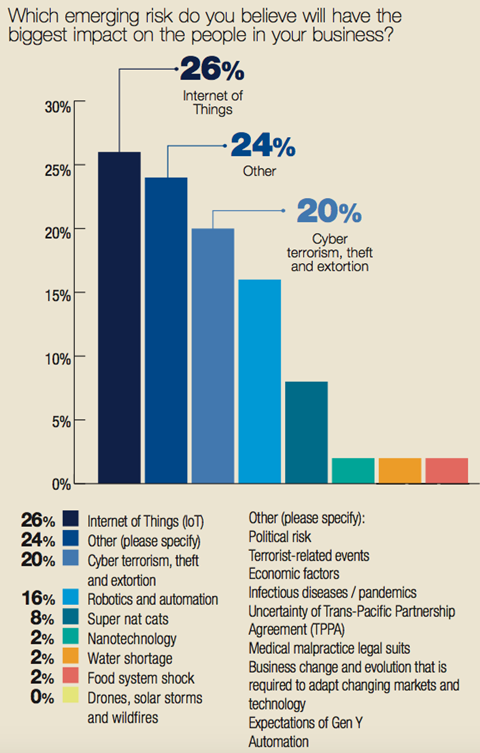

“Some research suggests that at least 20% of the workforce is going to be replaced by automation in the next five to 10 years,” says Zurich Hong Kong head of proposition, corporate division, Hassan Karim.

“Companies need to ask what this could mean not only for their business models, but also for their workforce. Could it lead to an employee backlash if they are replaced by machines? [And] what other elements of their business could be outsourced or become automated in the next five to 10 years?”

Already the substitution of capital for labour is moving beyond manufacturing to the service sector.

A simple example is in the supermarket: that of checkout staff replaced by a single employee to monitor a bank of self-service machines.

This kind of increased automation of service-based jobs could lead to an increase in employee strikes and corruption, says Karim.

And it’s not just lower-skilled jobs that are at risk, says Martin Ford, author of Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future.

“People with college degrees, even professional degrees, people like lawyers, are doing things that ultimately are predictable. A lot of those jobs are going to be susceptible [to being replaced by robots] over time,” he says.

Lazada Group’s head of group risk and internal audit, Gordon Song, offers a word of warning about robotics and automation.

“[Virtual reality], like any form of analytical tool or technique developed in the last two decades, will certainly be useful – but as with all tools, they will only be as useful as the people who created them.

“To be more precise, all models and tools require assumptions and variables, and these have proven to be limited in the complex world we live in. The ‘risk’ lies in over-relying on these tech-enabled tools, and moving too far away from human judgement which, in my opinion, is not replaceable.”

Ryan Tan, head of strategy and enterprise risk management at Singaporean public transport operator SMRT Corporation, agrees. He says a key risk is around the introduction of robots and other autonomous technology in an environment and infrastructure built for non-autonomous vehicles.

Regulatory bodies will play a key role in mitigating risks, he adds: “What sort of policies are they going to set up, and when are they going to do so in relation to the fast-evolving technology curve?”

Electronic caregivers

But it’s not all bad news.

Aon Risk Solutions Singapore chairman Geoffrey Lambrou says that the ability of robots to take on some jobs could prove a blessing, particularly for ageing populations.

“In Japan – one of the countries likely to be hit hardest by a greying population – the rise of the robot caregiver is already beginning, sponsored by the country’s health ministry. In Sweden, the GiraffPlus robotic system involves installing sensors throughout a home to monitor everything from falls to blood pressure,” he says.

In respect of the robotic revolution, a breakthrough moment will be the ability of robots to work together through connected systems, Lambrou adds. “Add the ability of all these machines – from manufacturing robots in factories to kitchen utensils in homes, fitness-monitoring wearables to driverless cars – to communicate with each other to the emerging ability of robot learning to adapt and improve, and we could be on the cusp of a new technological revolution,” he says.

No comments yet