Advice range from being “more defensive, canny and self-reliant”, to maximising “your online reputational presence”, experts gives top tips to corporates with exposures in high risk zones

Watching the news nowadays can be a disturbing experience. However, the relentless parade of tragedy is more than a reflection of editors’ attraction to bad news.

Beneath the white noise is a frightening truth: the world is becoming a more dangerous place.

“We are at a time now of extremely elevated geopolitical activity and violence,” says Charles Hecker, research director at Control Risks. In fact, it’s hard for us to look back and remember a time when so many areas were presenting such high levels of risk.”

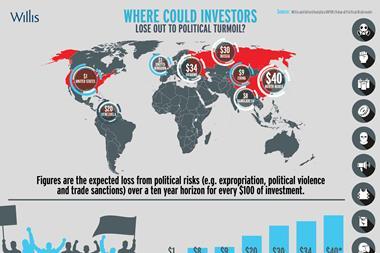

According to Maplecroft’s Political Risk Index, 36.5% of countries are now categorised as ‘extreme risk’ or ‘high risk’, rising from 32.5% in 2012. Charlotte Ingham, principal political risk analyst at the firm, says: “Although there are some notable improvements, generally speaking, the pace of that improvement is not sufficient to outweigh the speed at which a number of other countries – notably in the Middle East, North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa – are becoming much worse.”

Critical to understanding corporate exposure in this environment is appreciating the way governments and businesses now interact. “Companies care less and less about borders; they think about regions,” says Hecker. “But countries are caring more and more about borders and this brings the interaction between business and governments in sharp conflict.”

The relationships between populations and their governments has also undergone some profound changes, leading to pronounced civil unrest in previously ‘safe’ markets such as Brazil, Bulgaria, China and Turkey.

“We believe these situations are a result of similar factors,” says Jonathon Wood, head of global issues at Control Risks. “For the past 10 years, we have seen rapid economic growth, which was raising standards of living, but also expectations of what governments could and should be doing.

“Then, in the past two or three years, incomes have fallen sharply, which has brought into question the political settlement between governments and the new middle classes. Growth led to tolerance of state control, but when that growth disappeared, so did the tolerance.”

In addition, our enthusiasm for globalisation may have blinded many firms to the differences that persist underneath a universal enthusiasm for Gap and Apple.

“In a globalised economy, many players come from a liberal, market-driven background,” says Hecker. “However, others, such as Russia, don’t. Certainly, China doesn’t make any pretence of being an open democracy. This is a real source of friction. Sometimes, the Chinese play by the same rules as us, sometimes they don’t, and this is a source of risk.”

In these type of environments, companies need to be more defensive, canny and self-reliant. For example, international law and political advocate Robert Amsterdam advises firms to leverage their position for the benefit of local partners, because then it is far less lucrative for them to work against you.

“The other element is to maximise your online reputational presence,” he says. “This is counter-intuitive for many Western companies that are used to keeping their heads down, but that just plays into the hands of extortionists.

“Also, stop using the same advisers as every other multinational; hire local people with real contacts. In the end, personal relationships are everything, because you cannot rely on institutions.”

Stewart Rowles, assistant director at strategic intelligence and corporate security consultancy KCS, says he frequently finds links between hidden political entities and organised crime that involve secret networks and shadow directors when undertaking discrete non-conventional due diligence in Africa.

“The problem with political risk evaluation is that many do not understand the risks, the threats and the weaknesses,” he says. “The boards lack market, country and social-dynamic knowledge. It’s far more complex than many of them perceive. There is a distinct lack of money being spent in this area of risk.”

No one can afford to make assumptions that their investment is safe.“There is a perspective that as everything becomes more integrated everything becomes more similar and that just doesn’t happen,” says Hecker. “As a result, companies need to look at risk in a more comprehensive and systematic way. The days of thinking these problems don’t apply to us are over.”

Ingham says: “The companies that stand best prepared to mitigate the risks to their operations are those that are continually monitoring and responding not only to events in current ‘risk hotspots’, but are also horizon scanning for emerging issues in key markets.” This has the additional advantage of helping spot markets that present new opportunities.

Wood says: “We certainly need to be more sensitive to risk, but in a more subtle way. We need to know when to worry and when not worry.” SR

Developing risk: Nigeria

The Nigerian economy may be the largest in Africa, but an increasing risk arises of terrorism creating significant problems for investors.

Although 46 terrorist incidents occured in the first four months of 2014, in the three-and-a-half months from May to mid-August, 67 attacks were reported.

“This increased risk of terrorism is creating a host of challenges for investors in terms of ensuring they meet their duty of care to employees, with related implications of the cost of increased security to protect personnel and assets, and increased insurance premiums,”

says Ingham.

Although the threat is largely in north-east Nigeria, the group (Boko Haram) retains the ability to attack central and southern regions.

Supply-chain risk

According to Geoff Taylor, executive director, Willis Risk Solutions, firms should be mapping where their suppliers are and overlaying risk maps to enable risk professionals “to provide informed advice to the supply chain managers about aggregation of risk and potential bottlenecks”.

“Included in this type of software is the capability of identifying the values at risk and map exposures that also enable the insurance buying decisions to accurately reflect the exposure.

“Rather than merely buying blanket supplier extensions, you can buy what you need to avoid unnecessary cost and to give underwriters additional comfort that you know and understand your risk.”

More potential trouble spots

Nowadays, most of the world map looks like one vast potential trouble spot when viewed from a risk perspective. Out of the 162 countries covered by the Institute for Economics and Peace’s latest study, only 11 were not involved in a conflict.

In the weeks since the study was published, some regions have come to carry an even higher risk factor. US president Barack Obama has approved air strikes against the Islamic State both in Iraq and in Syria.

There is also speculation in Washington that the US will eventually send in ground troops against the Islamic State.

The call by Abu Bakr Al-Bagdhadi, the Caliph of the self-proclaimed Islamic State to all Muslims to join in the fight is having the effect of making that conflict spread to other states in the form of a growing terrorist threat.

Anticipating the return of British nationals who have trained in Syria, the UK raised its terror threat risk level to “severe” – only one level above “critical” – which would mean an attack is imminent.

Samantha Power, the US ambassador to the UN, is concerned that Syria still has chemical weapons and that any remaining stockpiles could end up in the hands of the Islamic State.

Some also believe that Russia, with the assistance of other countries, is also supporting the Islamic State. The wars in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Libya, etc are certainly keeping European leaders busy and distracted.

In an ironic replay of the Great Game, the diplomatic and intelligence rivalry that took place in the same region in the 19th century, Afghanistan is once again attracting the long-term interest of the world’s superpowers in the light of reports from US scientists that the troubled countries may be sitting on a treasure trove of rare minerals worth $1trn.

However, the region is only a side show for a Cold War-style greater game between the US, Russia and China. Having signed an important gas supplier contract with Russia, China will support Russia president Vladimir Putin while it suits. Combined, the two countries have a strong power base to heavily influence Asia as the balance of economic power shifts from the West to the East.

Indeed, some suggest the timing of the recent ramping up of tensions between China and almost all the countries with which it has territorial disputes may be have been designed as a show of power rather than any real intention to end disputes that have raged hundreds of years.

Europe cannot afford for Russia to cut off its gas supply as it is impossible to source a replacement supply within the next 10-15 years. Its leaders can make all protests they like, but they will have to think carefully about further sanctions or physical actions against Russia – and Putin knows it, which makes it likely that Russia will regain Ukraine in the not-too- distant future.

Stuart Poole- Robb is chief executive of business intelligence and cyber security adviser KCS Group Europe.

No comments yet