Global warming is making the Arctic more accessible to those looking to exploit its mineral wealth, but there is still much to be wary of

The news that oil giant Shell has been forced to abandon drilling in the Arctic this year sent its share price down and is discouraging other oil companies from investing in the region, according to Financial Times reports in September.

For many, the news has come as little surprise, highlighting the difficulties of operating in the polar region. But the fact that Shell has already invested some $4.5bn in its attempts also highlights the huge opportunities that many firms believe exist in this undeveloped region.

Climate change

Once inaccessible to all, climate change is opening up the Arctic in ways that seemed impossible even a decade ago. More ships than ever before are traversing the seas while on land, many are looking to exploit the huge mineral wealth.

According to NASA, the Greenland ice sheets are decreasing in mass quite rapidly. Data from NASA’s gravity recovery and climate experiment found Greenland lost 150km3-250km3 (36 to 60 cubic miles) of ice per year between 2002 and 2006.

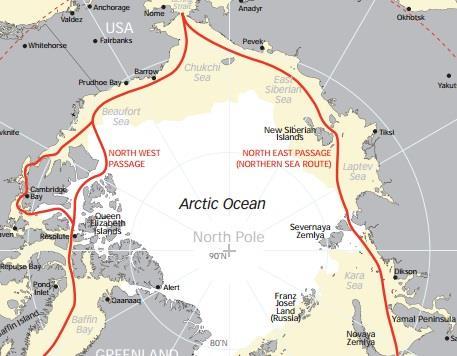

In August, the European Space Agency said that its satellite measurements “show we are heading for another year of below-average ice cover in the Arctic. As sea ice melts during the summer months, two major shipping routes have opened in the Arctic Ocean. In 2008, satellites saw that the northwest passage and the northern sea route were open simultaneously for the first time since satellite measurements began in the 1970s – and now it has happened again.”

Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme executive secretary Lars-Otto Reiersen says: “This year’s ice minimum does not come as a surprise, but the size of ice loss does.”

MIT professor Ernst Frankel explains: “The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet, largely because of the Albedo effect which causes darker surfaces such as land and water to absorb more heat than white surfaces such as snow and ice.

“If some water is exposed, heat absorption will accelerate and cause surrounding snow and ice to melt. This effect is largely responsible not only for the accelerated greening of Greenland, but also the accelerated melting of ice in the northern sea route and the north west passage.”

Something that many people may not have expected in their lifetime could now be a reality within the next decade or so – shipping may routinely traverse the region through the summer, and mineral exploration may begin in earnest.

Development so far

The potential for vessels to cross the Arctic is exciting news for the shipping industry, and for its millions of customers wanting cheaper and faster routes to market.

According to a report from risk management company DNV (Det Norske Veritas, which was originally founded to inspect and evaluate the technical condition of Norwegian merchant vessels), “Part-year Arctic transit may be economically attractive for container traffic from North Asia between 2030 and 2050. With a projected Arctic trade potential of 1.4m TEU in 2030, this amounts to a total of about 480 transit voyages across the Arctic in the summer of 2030. For 2050, the Arctic trade potential rises to 2.5m TEU and the total number of Arctic transit passages (one-way) in the summer of 2050 is about 850.”

Good news for a shipping industry currently under pressure to reduce its carbon footprint, the report also found that because of “shorter travel time and the need for a smaller fleet to carry the same amount of cargo between Asia and Europe by going across the Arctic compared with the route via the Suez Canal, CO2 emissions are reduced by 1.2 million tonnes annually in 2030 and by 2.9 million tonnes annually in 2050.”

The numbers so far are still small. For example, in 2011 there were just nine tanker movements in Russian waters, but there is a lot of interest in the north west passage, which would halve the distance between north-west Europe and the USA east coast to east Asia or the USA west coast. Not only does this save time and fuel, but it would reduce the need for vessels to transit either the Panama or Suez canals.

Five nations share control of the Arctic region, including Canada, the USA, Russia, Norway and Greenland/Denmark. Some of the biggest development opportunities come from oil and gas. So far, 146 fields have been discovered in Greenland, although only 23 are producing as yet.

Professor Frankel believes “the polar region may become the most important economic region” as the discovery of other mineral wealth starts to drive development. He cited Greenland as an example. “Greenland, while ice-covered until a few years ago, is now largely green and fertile. Roads, housing, airports and infrastructure are being developed.

“The polar region may yet trigger a new gold rush in human and economic terms and that time is not far away.”

The supply chain

The prospect of a new northern transit route must be music to the many thousands of firms dependent on global trade.

About 90% of world trade is carried by sea and, according to the International Chamber of Shipping, in the past four decades total seaborne trade estimates have quadrupled, from more than 8,000 billion tonne-miles in 1968 to more than 32,000 billion tonne-miles in 2008. And the figures just keep going up.

But there are risks, the Somali pirates are a menace in the northern stretches of the Indian Ocean, ships have accidents and strikes, or political unrest causes delays at either end of the journey. Being able to reduce journey times should help reduce the risks.

What could go wrong

Although the shipping industry sees itself as among the least environmentally damaging forms of transport, however, there are concerns about opening a trade route through the environmentally sensitive waters of the Arctic.

The Canadian government, as one of the five interested parties, has published reports on its concerns about increased development. But, as it says, much hinges on developing a treaty between the five countries involved.

The Arctic Council is a high-level inter-governmental forum to promote co-operation, co-ordination and interaction among the Arctic states and has a number of task forces to address key issues for the region.

Among these are task forces on search and rescue operations should a vessel get into trouble. Likewise, there is a task force to consider the impact of an environmental accident, such as an oil tanker running aground. This task force is also trying to address possible solutions to that risk.

In June, the US government allocated US$5m to the council’s environmental projects, following financial support from Russia. The funds will allow the council to work on pollution prevention measures.

As it stands, however, relatively few vessels transit the region and most have to be of an ice-breaking class, which limits the likelihood of regular container vessels.

Future development will need insurance. While companies like Shell may afford the billions of exploratory investment, other companies will want cover, particularly those using the area as a transit route for their otherwise insured cargo.

But as Clyde & Co partner John Flaherty says: “Insurers are not yet convinced that receding ice has reduced the risk of transiting icy waters. As salvage is almost impossible under Arctic conditions, insurers are well aware that the likely result of any collision will be an actual total loss.

“Even for vessels whose hulls are built to withstand such forces, navigating in ice is a huge exposure, reflected in the additional premium shipowners are liable to pay where their vessels trade in the Arctic, waters normally excluded under Institute warranties limits.”

He says that in speaking to underwriters, they have confirmed they would not normally consider insuring a vessel transiting the area unless it was of ice-class and assisted by ice-breakers. Additionally, conditions within the policy may stipulate that the vessel can only sail within certain timeframes and in specific weather conditions.

Flaherty says vessels that regularly trade in Arctic waters will elect to pay a premium for the entire season, while one-off journeys through the area will incur high premiums.

Development in the region is picking up, but it will be a while before the necessary infrastructure is in place to support shipping; services such as bunkering (refuelling) for example, as well as rescue and salvage facilities, are not currently in place.

Flaherty says the only solution at the moment is ensuring vessels have large fuel quantities onboard along with extra rations for crewmembers should the vessel get stuck in ice.

On top of that, the Arctic is largely uncharted waters. Detailed maps are yet to be drawn up, while another challenge will come from the long polar days of sunshine. This could disrupt sleep patterns for crew and, as marine underwriters will testify, many accidents are the result of human error.

All in all, the opportunities are there but it could still take the rest of our lifetimes to make the Arctic truly accessible.

No comments yet