High levels of violent crime are damaging prospects for growth in South Africa. Despite this, opportunities remain for businesses prepared to manage the security issues and take on a host of other potential risks

There was an enormous sense of pride across South Africa last year when it gained membership of the BRICS club, adding an S to the acronym covering Brazil, Russia, India and China.

But a year on, the country is still an underachiever. For a variety of reasons the rainbow nation is failing to realise its immense potential, leaving investors uncertain which way the country will go.

Could it become a key emerging economy alongside Brazil and Russia in the next decade? Or will it follow so many of its muddled African neighbours into managed decline? Or, worse, violent chaos?

The longer questions go unanswered, the more uncertainty itself seems to be South Africa’s defining problem. At present the country seems to be struggling despite itself.

But it doesn’t have to be like this, and the potential upsides of the country are significant. Despite a decline in production of gold and diamonds, South Africa is still the top producer of platinum, manganese and chrome, plus there are deep reserves of high-grade iron ore and coal.

Beyond natural resources, the tourist industry still has scope to expand and exploit its position as the gateway to Africa, offering western multinationals a foothold on a continent that includes half a dozen of the top 10 fastest growing economies, according to the World Bank.

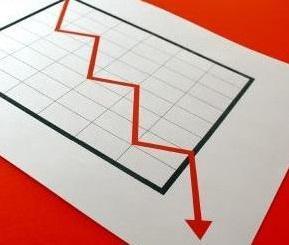

Yet the economy seems to have stalled. In 1995 South African GDP made up almost half of sub-Saharan Africa’s total, whereas in 2012 it accounts for less than one-third. Growth dropped from 5% to 3% between 2005 and 2009 and it is now one of Africa’s slowest growing economies.

Key points

- Economic/political uncertainty in South Africa continues to distract from plentiful natural resources.

- Growth dropped by 2% between 2005 and 2009, threatening its African leadership.

- Crime is a persistent problem even across the security system.

Every year the International Institute for Management Development compiles a list of 59 nations for its world competitiveness report. The latest list came out in May and this year South Africa was ranked 50th.

“Before then we were in the 30s and 40s, which is where we should be as the 32nd largest economy in the world,” says hospitality business Tsogo Sun Group’s director of risk, Gert Cruywagen.

“So we are now accorded a deep discount, and the reason given is that foreign investors are deterred from investing in South Africa on account of policy uncertainty here.”

With elections due this autumn, fears of political uncertainty are growing, adding to investors’ long list of questions about the country’s future.

We need the top 100 CEOs and other significant players in civil society to participate to create an inclusive economy

Gert Cruywagen

Tsogo Sun Group

The African National Congress is expected to win, but the party has yet to decide on its presidency candidate.

“We call this moment a second tipping point,” says Cruywagen. “The first tipping point occurred in the early 1990s [the end of apartheid] when we could have tipped into civil war but were saved from doing so by … a new constitution and an open, democratic election.

“We now need … the top 100 chief executives in the private sector, the unions and other significant players in civil society to participate to create an inclusive economy driven by a new generation of entrepreneurs and industrialists.”

So far this just isn’t happening. Cruywagen says the chances of South Africa becoming a premier league rather than a second division nation have changed from “70:30 18 months ago to 50:40” today.

“We do not have inclusive leadership, we do not celebrate our pockets of excellence and we have not changed our mindset towards entrepreneurs.”

Politically there is hope, but as with so many aspects of South Africa, this is tinged with uncertainty.

“Investors’ concerns have been allayed somewhat by Zuma’s presidency, which has not, as feared, sought to significantly alter the country’s business environment and shift economic policy to the left,” says Maplecroft associate director and Africa specialist James Smither.

However, there have been calls within the party to nationalise mines and speed up land reform. And newspapers have reported that a recent ANC conference descended into chaos and fistfights.

Stability at stake

The strength of the government and its ability to deliver stability is bound up in the success of the economy, so if it continues to stagnate there could be problems.

“Companies will still make money in South Africa, as they do in many developing economies,” says Cruywagen.

“But for the government it is a disaster. They won’t get the tax revenue they enjoy in the premier league, they won’t have the same access to foreign capital … We need another R750bn [€4.4bn] to sustain our water supplies.”

He says that in this scenario South Africa will be kicked out of the G20 and replaced by Nigeria - “which could overtake us by 2020 to become the largest economy in Africa” (see box, below).

Gateway to Africa?

South Africa’s status as the continent’s lead economy is under threat.

In terms of size alone, Nigeria has been growing at almost 7% for the past eight years, with Egypt close behind until the recent political upheaval.

Both countries have far larger populations than South Africa’s 50 million, at 170 million and 83 million respectively.

Elsewhere Ghana and Kenya are among those campaigning against South Africa to attract foreign multinationals looking for a base for African expansion.

General Electric, Nestlé, Coca-Cola and Heineken have all recently chosen Nairobi over Johannesburg.

But the elephant in the room in any discussion about South Africa is crime.

Cruywagen believes the country will avoid slipping into chaos - something he sees as a 1:10 probability - but its reputation for widespread, violent crime must be addressed.

“Although crime is falling, this is likely to remain a serious problem for the foreseeable future,” says Smither.

“The South African Police Service has responded to this threat with increased militarisation, and there are regular reports that the police are involved in extrajudicial killings and other abuses. Despite being largely free from terrorism and political conflict, South Africa thus remains a society heavily affected by violence.”

Smither continues: “This will almost certainly increase the cost of business operations. Most companies and many private residences rely on private security, partly due to a perception that the police are incapable of adequately responding to crime.

“However, this reliance creates the potential for reputational damage. Some private security firms have been accused of using inappropriate levels of violence as well as of committing human rights violations.”

South Africa remains a society heavily affected by violence

James Smither

Maplecroft

Risk and uncertainty is everywhere in South Africa, from its political elite right down to the township neighbourhoods.

At the same time, however, there is tremendous opportunity for those who are shrewd and well informed enough to be able to understand the situation on the ground - and to make the right call on the future.

Fuelling growth

Fuel supplies are essential for economic growth but, as in so many areas, South Africa is at a crossroads.

Until recently the country imported most of its oil from Iran. But sanctions have forced it into an increasingly expensive and competitive global oil market, which is likely to have an inflationary impact.

One possible solution is to increase the public stake in Sasol, a large publicly listed coal and oil company, and use this to reduce fuel prices as a form of subsidy. However, this would in turn probably cut profitability for competitors.

Meanwhile, fracking for natural gas is being considered as a way of unlocking untapped domestic potential.

But this is still a controversial technology and with the country already experiencing water stress, its potential to contaminate groundwater - as has happened in the USA - may halt further progress.

No comments yet