Labour unrest and political instability are key risks for companies operating in South-East Asia’s manufacturing hubs

An abundance of low-cost labour is a double-edged sword for emerging markets such as Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar. It can play a significant role in the growth of these economies as they industrialise, but it can also trigger instability and unrest if workers become exploited and lack the economic mobility they crave. Subsequent labour strikes can lead to production delays, which in turn cost retailers millions in lost profits or force them to reroute supply chains and seek out alternative producers.

Unfortunately, for a region that has captured a large proportion of low cost manufacturing from China over the last decade, sources of discord are not confined to the labour force. Political instability continues to impact the investment outlook, with the negative growth in Thailand’s manufacturing sector a prime example. Since the 2014 military coup, Thailand’s industrial production has hovered around 0% growth. The instability leading up to the coup resulted in severe disruptions in Bangkok as the government was paralysed by street protests between November 2013 and the May 2014 coup. While the steady output indicates that some investors have maintained confidence in the country as a manufacturing base, it has lost out to other regional competitors, namely Vietnam, which have attracted significant new investment as companies turned away from Thailand to what they consider more politically stable regimes.

Identifying where the next political crisis or major bout of unrest that may occur is therefore a challenge that companies operating in low-cost manufacturing hubs should be paying close attention to if they are to mitigate risks to the continuity of their supply chains. We take a look at what might be in store in a few of these key countries.

Cheap labour comes at high political cost

Cambodia has experienced rapid economic growth over the past decade, with exports increasing from US$1 billion in 2000 to US$5.8 billion in 2014, however, low wages and poor working conditions have undermined the benefits of increased investment. While agriculture and tourism remain the primary sources of employment for Cambodia’s labour force, the number of workers in the garment manufacturing sector has steadily increased from approximately 320,000 in 2009 to 600,000 in 2015.

Despite such rapid expansion and recent wage increases introduced by the government, incomes remain significantly lower than those in neighbouring Thailand or the Philippines, and many households risk falling back below the poverty threshold. Moreover, the protection of labour rights has not improved at the same pace as industrialisation. As a result, labour strikes and protests have become a regular feature of the social fabric in Cambodia over the past two years.

Political tensions are set to rise in the build-up to the 2018 general election, but the longer term risk of unrest in Cambodia may have been offset somewhat by the government-backed wage increases. Measures aimed at restricting factory employees’ ability to engage in labour strikes have also been implemented. While this may reduce the chances of unrest, it does leave companies sourcing in the country exposed to potential reputational and legal risks.

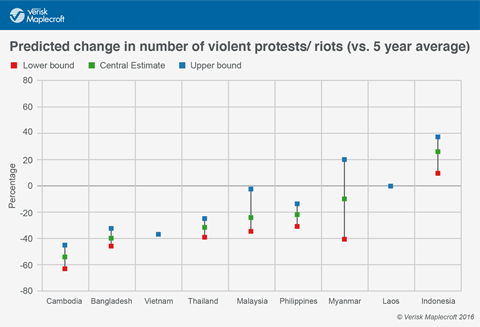

Low wages also leave workers vulnerable to other external economic conditions, increasing the risk of labour unrest as a result of downward economic pressure. Verisk Maplecroft’s Civil Disorder predictive model forecasts the likelihood that countries will experience a rising occurrence of civil disorder based on the analysis of several economic and social factors. For example, although Myanmar currently experiences more civil unrest than Thailand, the latter is considered a greater risk of increased unrest over the next year due to economic stagnation, a high perception of corruption and the continued rule of the military regime amid an oppressive environment.

The model illustrates that, for many countries, the combination of rapid changes to economic conditions can lead to a rapid increase in consumer prices leading to a greater risk of civil disorder, especially where wages are low. This combination is common among Asia’s emerging economies as low labour costs attract a rapid influx of foreign investment in low-skilled sectors. In many cases, governments are reluctant to raise the minimum wage in order to remain competitive. However, as investment continues to drive up GDP output and rising consumer demand by the growing workforce leads to price hikes for consumer goods. For example, in 2011 Vietnam experienced an annual price increase of over 18%, which was a key factor in the 850+ labour strikes that took place that year, as workers demanded higher wages. However, the country’s situation has stabilised thanks to low inflation and government efforts to establish minimum wages that are closer to the living wage.

Political stability underpins investment outlook

The experiences of Vietnam and Cambodia should provide a warning to Myanmar as it looks to attract more investment due to its competitively low labour costs. With the removal of remaining US economic sanctions in early October 2016, Myanmar is projected by the Asian Development Bank to experience GDP growth of 8% over the next two years. However, this will likely worsen inflation as the CPI (Consumer Price Index) has steadily risen since 2012 to 10.8% in 2015.

In addition to rising consumer prices, the country is already experiencing violence due to ongoing ethnic conflict and renewed religious tensions. While Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy government has touted poverty reduction as central to its economic policy, managing the balance between competitive labour costs and inflationary pressure will be crucial to continued progress towards alleviating civil disorder and ending communal violence.

As shown in the case of Vietnam, political stability may be under threat if authorities fail to translate the benefits of growing investment in manufacturing to better education and increased productivity, and improvements in labour rights protection. While emerging markets such as Myanmar will continue to provide growth opportunities for manufacturers, long-term gains will be difficult to achieve if investors fail to create sustainable value chains that provide workers with a means of economic mobility.

No comments yet