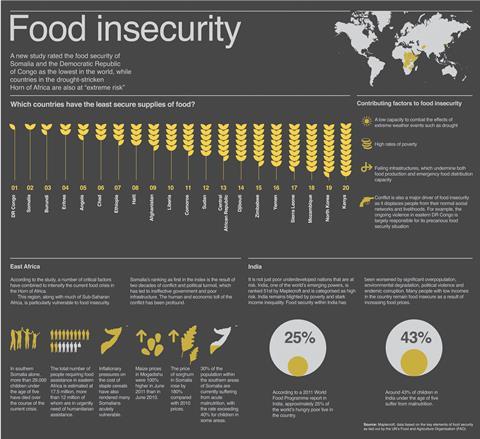

A new index reveals the extent of food insecurity worldwide and the factors exacerbating the problem

The world’s most severe food crises are being intensified by man-made factors and extreme weather events, a newly released food security risk index finds. Countries in the Horn of Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa are the most vulnerable to food insecurity, according to the index.

Maplecroft’s Food Security Risk Index (FSRI) assessed the stability and availability of food supplies in 196 countries. It measured the availability, access and stability of food supplies across all countries as well as the nutritional and health statuses of populations.

Rising global temperatures and a growing population are probably the two biggest factors leading to food scarcity, the report notes. The study indicates that Somalia, rated with the lowest food security in the index, has been ravaged by inflationary pressures on the cost of staple cereals. This, combined with the country’s ongoing political turmoil, has resulted in the disruption of trade and the destruction of transportation networks.

Thirty percent of the population within southern Somalia is suffering from acute malnutrition. In all of drought-stricken Eastern Africa, which has seen crop failures and livestock death due to the worst drought in 60 years, an estimated 17.5 million people currently require food assistance.

While the world’s underdeveloped nations such as DR Congo (ranked number 1 with Somalia), Haiti (ranked seven) and Zimbabwe (ranked 14) are topping the list, emerging economic power India was categorised as ‘high risk’ on rank 51.

While India’s food production is sufficient for domestic consumption, the nation’s food security situation is worsened by political violence and endemic corruption. Despite the country’s substantial economic growth over the past decade, approximately 25% of the world’s hungry poor live in India due to its severe income inequalities.

“As global demand for food grows due to rising populations, food security will take on increasing importance for governments and it needs to be on the risk agenda of multinationals,” Maplecroft chief executive Alyson Warhurst says.

In addition, food security can be a key driver of political and social volatility. Many sources point to competition for food and water as one of the key causes of the conflict in the Darfur region of Sudan, for example.

Scarce water and grazing land almost certainly fuelled tensions between Arab and non-Arab Sudanese nationals. Any area suffering from food or water stress has a higher risk of conflict, explains Maplecroft analyst Kimberlee Myers. “You’ll start to see more and more conflict, both violent and non-violent, as water supplies lessen and demand grows.” Improving infrastructure could help offset food security in developing countries.

Food security is also tightly wound up with access to clean water for drinking and using in agriculture. “For companies, it has a lot to do with where you’re operating. You need to know how much water is available to you and how much is available to the local population. You don’t want to be involved in a project where your company is taking water from the local population. That will end up being a reputational risk for you and also a possible water pricing risk,” Myers adds.

No comments yet